- On Student Success

- Posts

- Ignoring the obvious

Ignoring the obvious

An example of not seeing the elephant in the room when it comes to post-graduation earnings

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

One of the topics I’ll cover frequently at On Student Success is how well institutions help graduates secure jobs that pay reasonable wages. This isn’t only because I take an expansive view of student success, or because it’s the right thing to do, though both matter. Increasingly, post-graduation earnings are a key accountability standard for higher education. That’s certainly true in the US, where Gainful Employment and Financial Value Transparency introduced earnings premiums, later expanded in the OBBBA. Pressure is growing elsewhere, too, for example, the U.K. debate over “low-value” degrees. I expect that graduate earnings will only grow in salience.

The increasing importance of post graduation earnings poses real challenges for higher education. Labor markets, and pay levels, are largely outside institutional control, and the time horizons used in current metrics are short, often obscuring longer-term earnings trajectories.

A new post by in Labor Matters from Gad Levanon, Joseph Winkelmann and Mels de Zeeuw at the Burning Glass Institute highlights the danger of relying on short-term signals to measure value. Using liberal-arts institutions as an example, they show how a longer view can reveal substantial changes in earnings. That’s an important point. But the post underplays a critical factor: broader social trends and biases that shape earnings, especially the impact of gender on depressing wages.

This matters. Higher education should do more to ensure its credentials provide a remunerative path into the workforce. Institutions should strengthen career preparation and support the school-to-work transition. But some forces are beyond their control, regional pay differences (rural vs. urban) and gender pay gaps among them. Yet new accountability rules often ignore these differences. Over at On EdTech, Phil has written about pay variation across regions even as earnings are measured at the state level. Here, I want to underscore the gender dimension, using Gad, Joseph & Mels’ post as a clear example.

There is something different about Bryn Mawr, I cant quite pinpoint it

To illustrate how earnings growth unfolds over time, Gad, Joseph & Mels examine U.S. liberal arts colleges, primarily undergraduate institutions that offer broad, interdisciplinary education across the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, and arts rather than vocational or professional training.

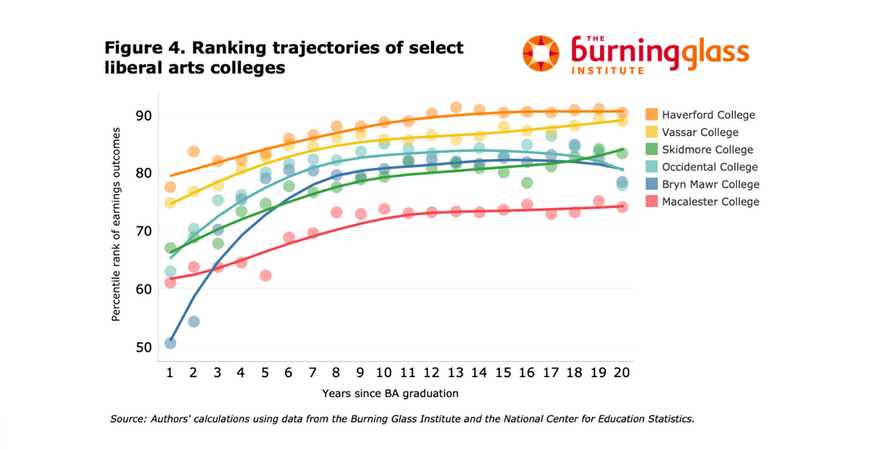

They analyze post-BA earnings at a selected group of liberal arts institutions over a 20-year period. For those familiar with these colleges, one pattern stands out: Bryn Mawr graduates earn relatively little right out of the gate and improve dramatically over time, yet still finish second-lowest in the sample over the long term.

Bryn Mawr graduates do noticeably worse than Haverford graduates, by nearly 30 percentage points, despite the schools’ close proximity and extensive cross-registration. The most salient difference is that Haverford is coeducational, while Bryn Mawr admits only women.

Could the earnings gap simply reflect gender? Gad et al do not consider gender in their analysis, leaving a key explanatory variable unaddressed.

Our regressions already control for race, gender, and undergraduate major at the individual level, as well as average SAT scores by institution as a proxy for academic selectivity.

I’m not sure how you “control for gender” when nearly 100% of the sample are women. I’m not a quantoid, but I’m still calling bullshit on that. Gad et al instead point to factors like family income and graduate-school enrollment, and both are likely relevant.

But the biggest driver of lower early (and even later) earnings is gender. Women earn about 84 cents for every dollar men earn, and that headline number understates how pervasive the barriers are. As Kweilin Ellingrud, Lareina Yee, and Maria del Mar Martinez explain in The Broken Rung which is well worth a read, the structural hurdles begin at the first step up to management and compound over time

Women who make up 59 percent of college graduates in the United States immediately lose ground, representing only 48 percent of those entering the corporate workforce. At the pivotal moment when the first promotions to become a manager happen, the odds of advancement are lower for women. For every one hundred men, only 81 women receive that same promotion opportunity.

Because these early differences compound over time it becomes difficult for women ever to catch up with men in earnings and experience.

Why this matters

Colleges and universities are increasingly held accountable for their graduates’ workforce outcomes, and in general I think that’s a good thing. But some issues are beyond higher education’s control, at least not single-handedly or in the short term, and one of them is the wage premium associated with being male. That reality disproportionately affects certain institutions, such as women’s colleges and campuses with a heavy nursing focus.

I don’t have a neat solution. Greater awareness could lead to better ways of calculating earnings premiums and, ideally, to more equity in the workforce. But I suspect those hopes may go unrequited, at least for now.

What the post got right

There’s also a geographic factor that Gad, Joseph & Mels overlook. Part of why Macalester graduates earn less than graduates of some other colleges may be location. Macalester is in Saint Paul, Minnesota; the others are on the coasts, where salaries are typically higher.

That said, the post’s main argument is spot on and very useful: looking at earnings too soon after graduation can obscure how graduates from some institutions start lower but see substantial gains over time.

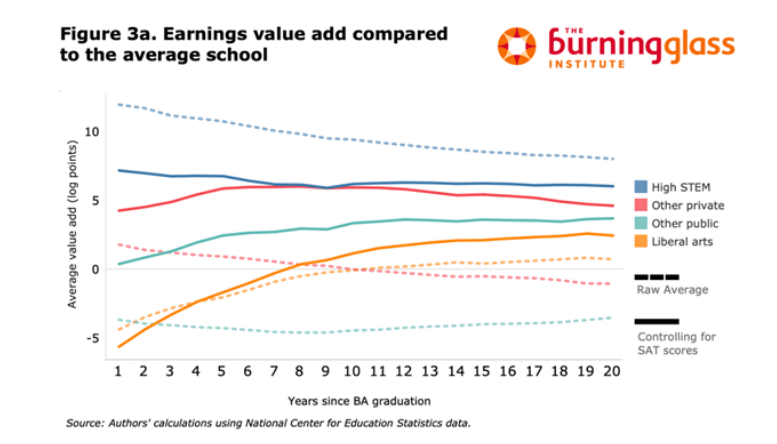

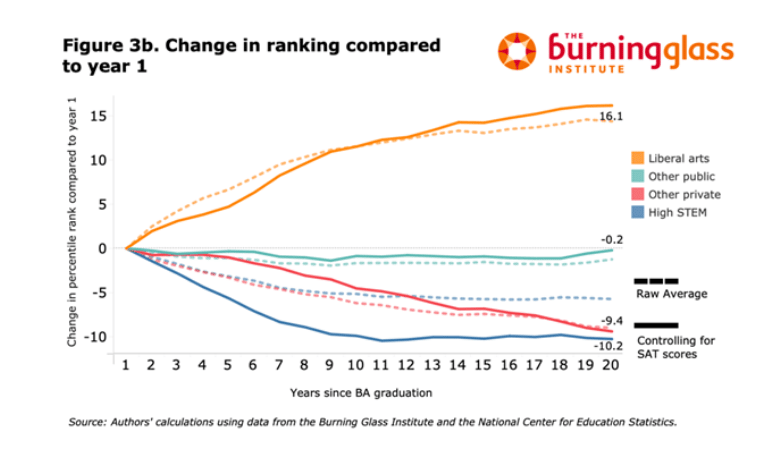

The focus on early years can be especially damaging for liberal arts colleges (LACs). LAC graduates generally earn less than their peers, in part because they are more likely to enter lower-paying but socially valuable fields such as education, the arts, and nonprofit work. Especially after adjusting for student selectivity—using metrics like average SAT scores—graduates from LACs appear to dramatically underperform in early-career earnings. This depresses their position in school rankings and may reduce their appeal to prospective students.

However, much of this underperformance is concentrated in the early years after graduation. Over time, LAC graduates tend to catch up—narrowing or even closing the earnings gap with peers from other institutions. This report investigates how the earnings of different college types evolves from early to mid-career, with a particular focus on liberal arts colleges.

Earnings among liberal arts college graduates tend to be lower overall, especially when controlling for SAT scores, a proxy for academic aptitude at entry, because these graduates disproportionately pursue social-impact careers. Yet their rate of earnings growth over time is remarkable.

To me, this speaks to the quality of liberal arts education and the “learn-how-to-learn” capability students develop. It also underscores the problems with relying on short-term income measures, as most federal and state earnings premiums do. Ideally, earnings metrics would take a longer view and account for graduates’ capacity for growth over time.

Parting thoughts

Higher education faces plenty of challenges. Some are internal and self-inflicted; others, like gender-based earnings disparities, are societal. Punishing institutions for the latter is deeply problematic and ultimately harmful to society.

Full disclosure: my spouse graduated from Bryn Mawr College, majored in Medieval Studies, ran the radio station at Haverford College, and earns substantially more than I do.

The main On Student Success newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.