- On Student Success

- Posts

- Two Problems I have With Durable Skills

Two Problems I have With Durable Skills

Missing the most important one, and mis-framing the rest

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

If I’m honest (as the British are wont to say), I actually have three problems with durable skills. The third, and least important, is simply what to call them. The labels—durable skills, soft skills, twenty-first century skills—are all circling the same set of ideas, but each comes with baggage. Picking one isn’t just a neutral choice; it’s a declaration of allegiance. And in doing so, you risk alienating those who prefer a different label, which only distracts from your mission and muddies your message.

Still, this is a minor irritation compared with the bigger issues. First, these skill sets almost never include the most essential one—learning how to learn. Second, they’re almost always framed as relevant only to the workplace, rather than to higher education itself. I would argue the opposite: learning to learn is the most important, and indeed the most durable, of all the durable skills. And the rest are not just assets for the workplace but critical components of student success while students are still enrolled.

And for the record, I’m Team Durable Skills, at least for now.

Learning how to learn

You can hardly open a newsletter or an article in the higher education trade press without stumbling across yet another list of the “top ten durable skills” graduates supposedly need to succeed in the workplace. And, almost invariably, the underlying message is that most graduates don’t have them.

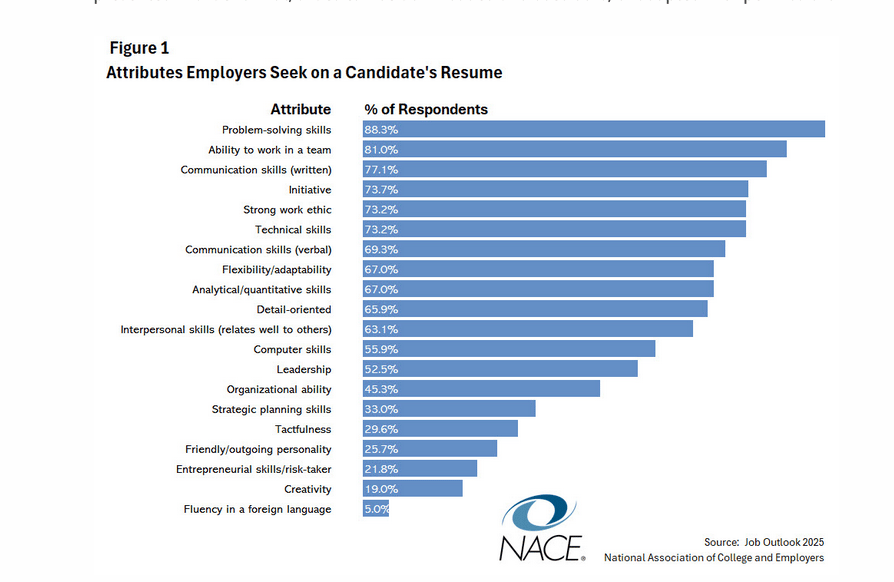

You know the lists: critical thinking, communication, leadership, and so on. This recent example from the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) is fairly typical, but by no means unique. There are plenty of others just like it.

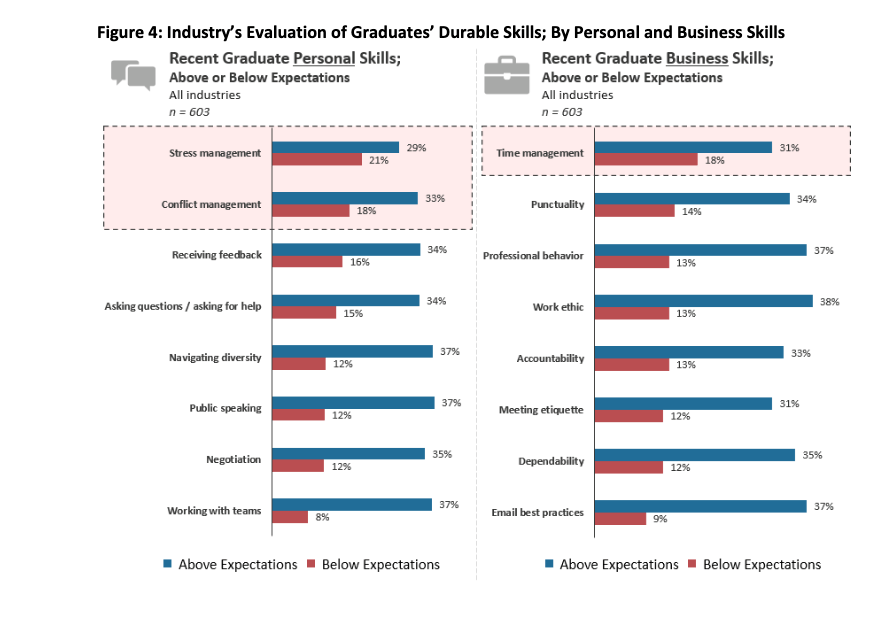

That’s quite a lot of skills. This particular list, based on a survey of employers in Utah, not only runs long but also gets very specific.

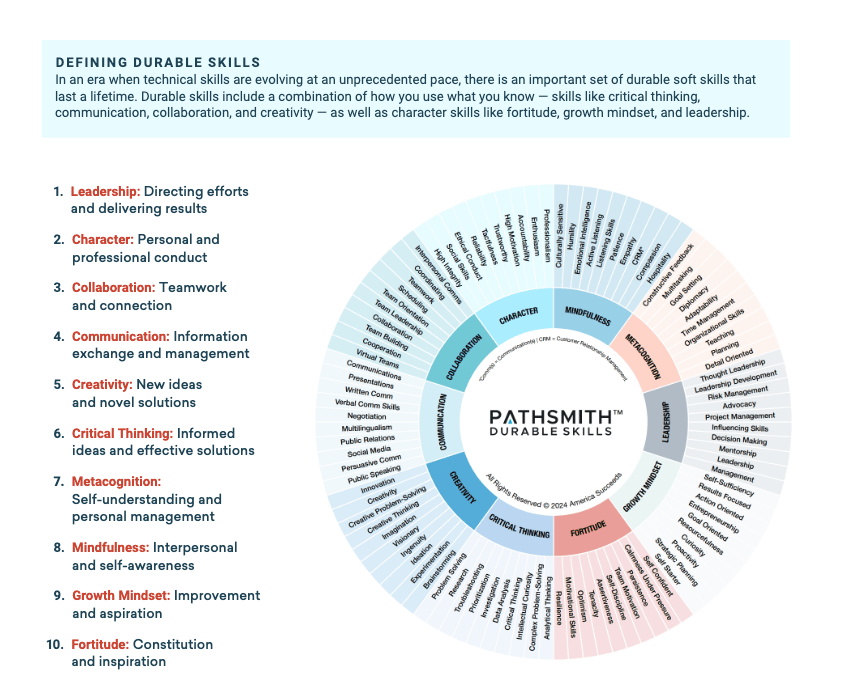

But even with their length, what most of these lists seem to leave out is the ability to learn how to learn. Even this massive compilation doesn’t appear to include it, at least as far as I can tell, though I admit I lost focus somewhere around the roulette wheel.

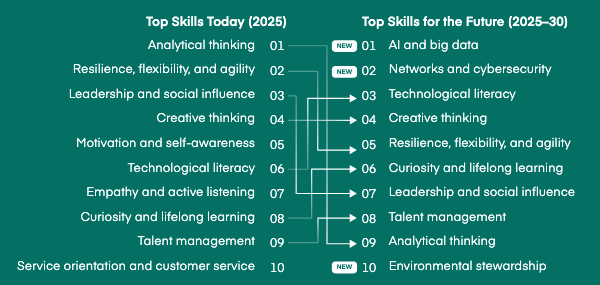

This list from the business school accreditor AACSB gets a bit closer by including curiosity and lifelong learning. But even those are framed more as a mindset, an orientation or openness to learning, than as the concrete skills needed to take on a new topic and develop real proficiency.

So why is this important?

The absence of the meta-skill learning how to learn from these lists is troubling for several reasons.

First, we cannot predict what specific skills or knowledge today’s graduates will need in a rapidly changing, technology-driven workplace. The only certainty is uncertainty. That’s why the most durable skill of all is the ability to learn itself. Every other durable skill, problem-solving, collaboration, adaptability, ultimately depends on it. Equipping students with the capacity to acquire new knowledge and abilities quickly, in context, and often on the fly is the surest way to prepare them not just for their first job, but for a lifetime of change. These skills are meant to be durable i.e. lasting.

Second, by sidestepping this central issue, the creators of these lists often overcompensate with ever-expanding inventories of skills, many of which are highly job-specific, prone to obsolescence (one list above even included “email best practices”), and not universally relevant. Everyone, however, needs the ability to adapt and grow.

Third, the vagueness of popular terms like critical thinking may reflect an attempt to gesture toward this deeper need without naming it directly. By failing to foreground learning how to learn, we risk producing lists that are diffuse, confusing, and less useful, and, more importantly, risk leaving students under-prepared for the realities of both work and life.

Why is learning to learn omitted from lists of durable skills so often?

I don’t have a neat answer for why learning how to learn is so often omitted from lists of durable skills, but I have a few hypotheses.

The ability to learn is abstract and less tangible than skills like communication or leadership. Policymakers, employers, and curriculum designers tend to favor skills that are easier to observe or assess.

These lists are often prone to overlap. Even when they aren’t as sprawling as the roulette-wheel catalogues, many frameworks already include elements that are really components of learning how to learn, curiosity, deep listening, the ability to process feedback.

The ability to learn is often assumed rather than explicitly taught or questioned. Educators and employers may take it for granted that students naturally acquire learning skills simply by progressing through university. In reality, many students struggle to learn effectively, and these abilities are unevenly distributed across populations.

Finally, many durable or soft skills frameworks are based on employer surveys. Employers understandably highlight the skills they see as immediately useful in workplace contexts such as teamwork, communication, rather than long-term meta-skills like the capacity to keep learning, which ultimately underpin career growth.

Which brings me to my second problem with durable skills: the way they are almost always framed as workforce-only, rather than as essential to student success while still in higher education.

Why workforce only?

Too often, conversations about durable skills frame them narrowly as competencies students will need only once they enter the workforce, rather than as capabilities critical for success during college itself. That framing is deeply problematic for several reasons.

Creates a false dichotomy between school and work. Treating durable skills as something important only in the workplace implies the two are unrelated. This contributes to confusion about how these skills should be developed and fuels the general inaction that surrounds the topic.

They are essential for student success. Many of the skills commonly listed such as time management, communication, resilience, adaptability, help-seeking behavior, are not just nice-to-haves but essential for navigating the challenges of higher education. Ignoring them while students are still enrolled undermines efforts to improve retention and persistence.

Missed opportunity for contextual practice. If students only begin to practice and value these skills after they leave college, they miss the chance to develop them in a lower-stakes, supportive environment. Group projects, campus leadership roles, and co-curricular activities provide natural laboratories for building teamwork, communication, and problem-solving before these skills become career-critical.

Reinforces narrow accountability metrics. Framing durable skills as workplace-only reinforces the idea that student success is measured exclusively by job placement, rather than by how well students thrive, persist, and grow during their studies. This risks narrowing institutional accountability and devaluing broader educational missions.

Exacerbates inequities. Students from historically under-served backgrounds may enter higher education without the same exposure to informal skill-building opportunities (e.g., internships, professional networks). If institutions minimize the importance of durable skills until after graduation, these students face compounded disadvantages both in college and in the job market.

Deepens the curriculum–co-curriculum divide. Treating durable skills as “for later” perpetuates silos between academic and co-curricular life. In reality, embedding these skills into coursework, advising, and student activities creates a more holistic, integrated experience.

Occasionally skills that students might need for college get a mention, but not very often. More frequently self-directed learning is acknowledged as an important soft skill for students, but it is often treated narrowly and in a remedial context. While self-directed skills lean toward the broader idea of learning how to learn, they are typically framed in mechanical terms. Further, in research I conducted some years ago with Chuck Dziuban, Flora McMartin, Patsy Moskal, Alan Wolf, and our late friend Josh Morrill, we found that such skills are held by only a minority of students, and often function as coping mechanisms driven by time pressure rather than as durable learning abilities.

Parting thoughts

If we are serious about preparing students for success after graduation by helping them develop durable skills, then we need to place greater emphasis on learning to learn, the ultimate “uber-skill”—and on cultivating and practicing those skills throughout their time as students. Just as importantly, educators need to take a more active role in shaping what we mean by durable skills, rather than leaving that definition entirely to employers.

The big question, of course, is how we actually teach students how to learn and embed durable skills into the curriculum in ways that feel meaningful and sustainable. I don’t have the answers yet, despite reading books by people like Barbara Oakley and even repeatedly trying (and failing) to complete the MOOC on the subject.

But exploring this will be the topic of some future posts.

The main On Student Success newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.