- On Student Success

- Posts

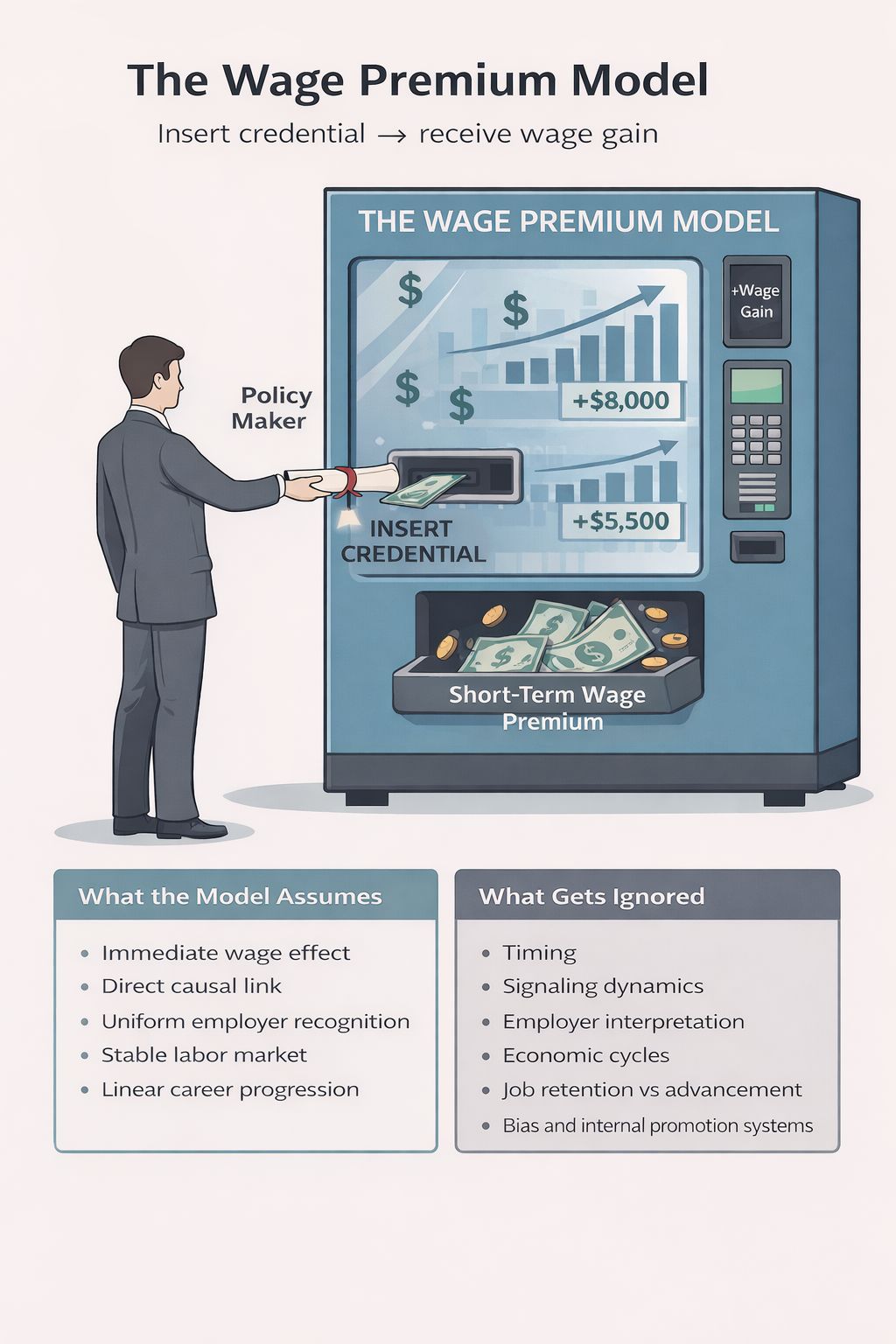

- One Problem With Treating Non-Degree Credentials Like Vending Machines

One Problem With Treating Non-Degree Credentials Like Vending Machines

When better data still asks the wrong question

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

Over the past several years the discussion on non-degree credentials has been a story of two extremes. On the one hand, there was a lot of hype. Across multiple contexts, they have been seen as solutions to all kinds of problems. They are touted as a remedy to the high cost of higher education and a way to get students into the labor force more quickly as well as an important source of new revenue for higher education institutions.

On the other hand they have been demonized as low quality (particularly in the online versions) and a way that students would be short-changed by low quality, overly quick credentials that would bear little fruit in terms of payoff.

Finally we have a correction to these skewed ways of thinking about non-degree credentials in two excellent recent reports — Brookings’ Market Value of Non-Degree Credentials and the Burning Glass Institute’s Measuring What Matters. Both are empirically serious and methodologically impressive. Both complicate the hype and the gloom, and both deserve credit for grounding the debate in data. They mark an important maturation of the debate. But maturation is not the same as completeness.

Both reports improve the measurement of credentials. But they still measure the wrong thing. Even in their sophistication and rigor, they share a common assumption: that the value of a credential can ultimately be captured through relatively short-term economic return. That assumption is the problem. It treats higher education like a vending machine: you obtain a credential and receive a wage boost. This means they don’t capture the reality of how jobs work but, worse than that, our measurement system reshapes the ecosystem. Everything becomes about the wage premium, and we never fully understand how non-degree credentials work or how to improve them.

The Correction Was Necessary

Brookings provides a careful analysis of wage outcomes associated with non-degree credentials (NDCs). The headline is not that credentials are worthless. It is that returns are uneven.

The strongest wage gains appear among individuals without bachelor’s degrees. Returns are higher when credentials are directly aligned with a worker’s occupation (or job-relevant as they phrase it). For degree holders and experienced employees, the marginal wage benefit of additional, job-irrelevant credentials is limited.

Controlling for a variety of worker and labor market characteristics, we find that

workers’ first job‑relevant NDC is associated with a wage premium of about 3.8%

compared to workers without an NDC, more than double the 1.8% premium for a first job‑irrelevant NDC. Additional NDCs generate gains only when they are relevant to the worker’s occupation: Each additional job‑relevant NDC is associated with roughly a 1.0% marginal increase in wages, while accumulating irrelevant NDCs yields no significant returns. [snip]

For workers without a bachelor’s degree, the first job-relevant NDC is associated with a wage premium of 6.8%, nearly double the premium for comparable college graduates, and additional relevant NDCs also yield larger marginal gains for non-degree holders. Early-career workers likewise experience much stronger benefits than experienced workers: A first job-relevant NDC is associated with roughly a 6% wage premium and additional relevant NDCs with more than 2% higher wages per NDC, while accumulation effects for experienced workers are close to zero.

This is an important corrective. It pushes back against the idea that simply stacking credentials will reliably produce upward mobility. It also complicates marketplace strategies built around the assumption that every additional badge meaningfully moves the needle.

Burning Glass takes the debate further. Rather than focusing only on immediate wage gains, they broaden the definition of value to include career mobility. 6% of NDCs payoff immediately (what they call a Launchpad), about 8% allow employees to move to better positions in the same field (Promotion Catalyst) or in a new field for 17% of them (Lateral Move). But the majority of NDC holders, 69%, are unfortunately still stuck in the Dead End category with no wage payoff. In other words, only about one-third of credentials meaningfully change a worker’s trajectory, while the majority function as economic dead ends.

They also extend the analysis to longer term advancement, looking five years down the road to see which of these types of moves pays off. Things shift a little but not much. 65.5% of NDC holders are still in the Dead End category, with low wages, and low onward mobility.

Even with a broader time horizon, the underlying logic remains the same: credential → economic payoff. The frame has widened. The assumption has not.

The Signaling Story We Don’t Quite Name

One of the most revealing findings in the Brookings analysis is that returns are strongest for workers without degrees. While the Brookings report talks about signaling, it uses that designation for NDCs that are job-irrelevant. But their research shows that all NDCs have a signaling function and that should fundamentally change how we think about what these credentials are doing.

If non-degree credentials deliver their largest wage gains to those without bachelor’s degrees, that suggests that an important part of their value lies in signaling. For some workers, credentials function as threshold markers — signals that help them cross initial labor market barriers. They make a candidate legible to employers. They open doors. But once inside the labor market, additional credentials deliver diminishing returns unless tightly aligned with specific roles.

That has implications for how institutions design and market credentials. It also raises questions about the long-term viability of models built on the idea of continuous stacking as a universal strategy. Credentials may be most powerful at points of entry or transition. That is different from being universally transformative.

The Problem With Transactional Models

But my biggest problem with Brookings and the Burning Glass research is that as good as it is, it still hugely oversimplifies the way that the workplace functions. They are both ultimately based on a model where an investment in a credential pays off or doesn’t pay off in a wage gain, depending on the nature of the credential itself. But the workplace doesn’t work like this. Labor markets are messy, path-dependent, and shaped by timing, recognition, and context in ways that wage data alone cannot capture.

A worker may complete a credential just as their firm freezes promotions. The value of that credential does not disappear, but its wage signal is delayed. A short-term earnings study may record “no return,” when the issue is timing, not irrelevance.

Another worker may use a credential not to earn more, but to avoid earning less. In volatile industries, maintaining employability can be the return. Preventing displacement does not show up as a wage bump, but it may be economically decisive.

In some cases, credentials function less as skill accelerators and more as signals. Brookings finds stronger returns for those without degrees. As noted earlier, part of this pattern reflects signaling dynamics.

Few workplaces exhibit unrelenting rationality or instrumentalism. Networks and connections matter as does who gets noticed and why. Wage raises and promotions depend on these factors as on qualifications and credentials.

Employer recognition also varies. A credential’s value depends not only on what it teaches, but on whether hiring managers understand it, trust it, and know how to interpret it. In one labor market, a certificate may open doors; in another, it may be invisible.

And then there is simple human bias. Promotion decisions are not purely skills-based. They are shaped by relationships, networks, and institutional politics. Credentials operate within those systems, not above them.

None of this means that credentials lack value. It means that value unfolds over time, and often indirectly. It is cumulative, contextual, and contingent. The model used in so much of the debate about the ROI of credentials, including the Brookings and Burning Glass work, is appealing because it is measurable. But it is a poor description of how careers actually work.

And the problem is not just how we measure the payoff of credentials. It is how those measurements shape design and narrative. Measurement influences design. Design shapes perception. And perception ultimately drives funding and policy.

The Wage-First Feedback Loop

So it is not just conceptual. It’s structural. Our measurement system reshapes the ecosystem. This happens because there is an un-virtuous cycle or feedback loop at work. Policy increasingly demands measurable economic return. Workforce funding proposals, state ROI dashboards, and federal accountability frameworks rely heavily on short-term earnings thresholds. In response, researchers produce wage-based analyses. Those analyses reinforce the policy logic. Institutions then design credentials to optimize for those metrics. The debate narrows and becomes increasingly sterile.

If the vending-machine model describes how we think credentials work, the wage-first feedback loop explains why that model persists. The more we define value in short-term wage terms, the more we encourage a system that treats credentials as instruments for immediate income boosts rather than components of longer-term career development.

The cycle is understandable. Wage data are clean. Policymakers want clarity. But clarity is not completeness. The result is a policy environment that rewards short-term wage optimization rather than thoughtful pathway design.

We see this feedback loop in action across multiple states. In Alabama, wage-matched outcomes guide scholarship targeting and pathway development. Arkansas and Colorado have embedded ROI and employment metrics into funding formulas and reporting requirements, meaning colleges essentially compete on wage-linked outcomes. Louisiana mandates annual ROI analyses even for high school credentials, extending the wage frame earlier in the pipeline. Texas law now classifies credentials based on positive ROI and labor-market demand, steering program portfolios toward wage-linked definitions of value. Virginia’s FastForward evaluations embed continuous ROI assessment into short-term occupational training. These policies don’t just measure outcomes, they reshape how states define, fund, and prioritize credentials around wage-centric metrics.

Why This Matters

If we care about designing credentials that actually change trajectories rather than simply clear accountability thresholds, these are the questions that matter.

• For whom?

• Under what labor market conditions?

• At what career stage?

• With what employer recognition?

• Over what time horizon?

We should pay attention to whether credentials help workers enter fields, maintain employability, or navigate transitions, even if those outcomes do not show up immediately in wage data.

If two-thirds of credentials deliver limited economic mobility, that is not simply a verdict on credentials. It is a design challenge. It suggests that alignment, signaling clarity, employer engagement, and pathway sequencing matter far more than volume.

Until we answer the questions about for whom and under what labor conditions credentials work, higher education will struggle to design programs that deliver real value. Instead, we risk remaining stuck in a cycle of chasing wage metrics that will inevitably disappoint. We need to expand the argument and the measurements in order to design better credentials.

A Concluding Thought

There are clearly challenges with NDCs and they need to be improved. The problem is not that non-degree credentials fail to deliver value. The problem is that we keep trying to measure that value in ways that assume careers unfold in neat, linear increments, which unfortunately they do not.

Policy operates on annual cycles. Research often focuses on short-term wage shifts. But careers are shaped by timing, signaling, employer recognition, and economic cycles that unfold over years.

If we continue to evaluate credentials as though they were vending machines — put one in, get a wage bump out — we risk misjudging their role, mis-designing programs, and misleading students. Brookings and Burning Glass have made the debate more rigorous. The next step is to make it more complete.

ROI in terms of wage gain is not the wrong question. It is simply too small a lens for understanding how careers actually unfold.

As always, please share this with anyone who may find it interesting. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.