- On Student Success

- Posts

- Surveys, Samples, Signal and Noise

Surveys, Samples, Signal and Noise

What the AAC&U report on employers perceptions reminds us about evidence

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

I have a modest political pin collection, and one of my favorites dates back to the 1936 US presidential election, when Alf Landon of Kansas ran against the incumbent Franklin Roosevelt. It’s a small artifact from one of the most lopsided elections in modern American history, and a useful reminder of how badly conventional wisdom can misread reality.

This image is from one for sale on Etsy - my photography skills being what they are

Prior to the election, The Literary Digest ran a large-scale survey. Having correctly predicted the winners of the previous five presidential elections, the magazine was widely trusted as a political forecaster. Based on 2.38 million responses (equivalent to 18.7 million people in today’s currency!), it confidently predicted that Landon would win in a landslide.

He didn’t.

Instead, Landon carried only Vermont and Maine, winning a mere eight electoral votes, one of the lowest totals in U.S. history.

Many explanations have been offered for this failure, but most come down to two related problems.

First, the magazine’s readership skewed far more Republican than the general population.

Second, the survey relied on voluntary participation, meaning it captured the views of people who were especially motivated to respond rather than a representative cross-section of voters.

The result was a massive dataset that was systematically misleading.

Which is to say: surveys can be enormously valuable, but their findings, and the conclusions drawn from them, must be interpreted with care.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately, and a recent survey report from AAC&U offered a timely reminder of why survey-based evidence deserves close, critical scrutiny.

A good survey, read carefully

AAC&U recently published a fascinating, and methodologically sound, report on employers’ attitudes toward the skills of recent graduates. It is a strong piece of work, with many interesting and carefully presented findings. This is exactly the kind of survey we need more of in higher education.

One of the biggest surprises for me was the extent to which employers value higher education’s role in educating the whole person. In particular, they see universities as responsible not only for preparing students for work, but also for helping them become informed citizens. Fully 94 percent of employers say it is very or somewhat important for institutions to help students develop as informed citizens—the same proportion who believe it is important for universities to prepare educated workers for the economy.

This runs counter to the common impression that universities should focus narrowly on workforce skills and immediate job preparation.

Less encouragingly, the survey also revealed more ambivalent views about different kinds of out-of-classroom learning experiences. Internships, as expected, remain highly valued. But employers’ relatively muted enthusiasm for more widely accessible experiences—such as on-campus employment, senior projects, and study abroad, is more concerning, particularly given how much more accessible many of these are to students, compared to internships.

Who you ask changes the answer

he AAC&U report is both valuable and fascinating, and under normal circumstances I would spend much more time unpacking its details, especially because many of its findings run counter to what we often hear in the media as received wisdom.

To be clear, this is a well-executed survey, with a strong sample and careful, thoughtful analysis. It is well worth reading in full and discussing more widely.

One aspect of the report, however, stood out to me in particular. The way AAC&U disaggregated its data served as a useful reminder of how much survey findings depend on whom you ask. This became especially clear in their treatment of one of the most contested questions in higher education today: how well institutions are preparing students for the workplace.

Contrary to much of the current prevailing narrative, a majority of employers in the AAC&U survey believe that higher education is doing a reasonably good job of preparing graduates for work.

But what is most striking are the breakdowns by age and political affiliation. Republicans and Democrats are remarkably similar in their views on this issue, while Independents emerge as a clear outlier.

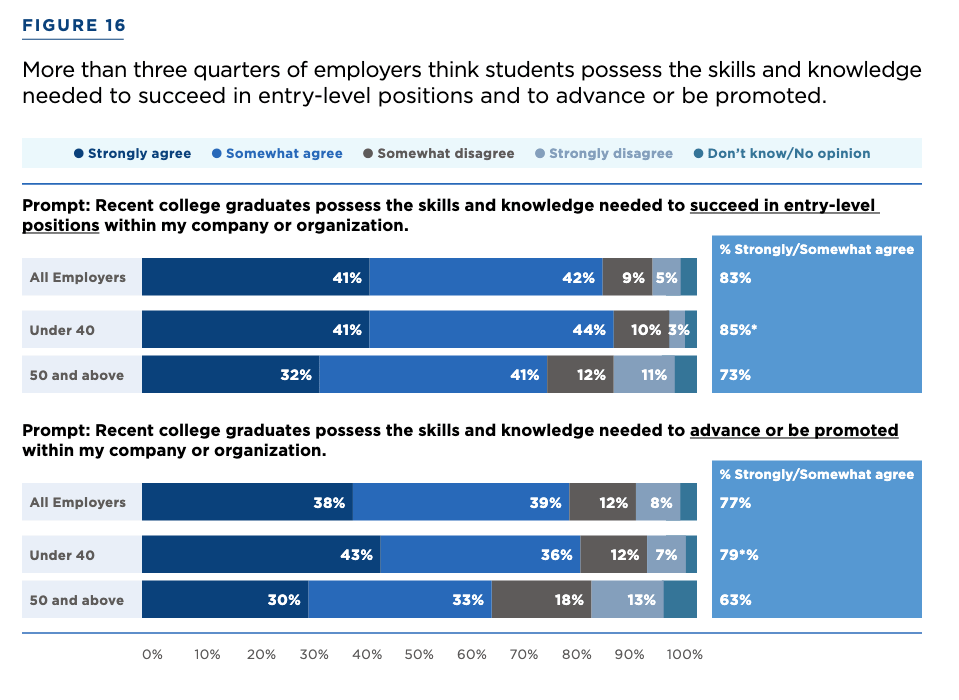

There are also substantial differences by age. Employers aged 50 and older are far more critical of how well higher education prepares students for the workforce. This age-based divide becomes even clearer when AAC&U asks more focused questions about the skills and knowledge needed to succeed in entry-level positions and to earn promotion.

There is a 12-point gap between employers under 40 and those over 50 in their assessments of how well students are prepared for entry-level jobs, and a 16-point gap in their views of whether recent graduates have the skills needed for promotion. Both differences are substantial, and too large to dismiss as statistical noise.

Why do we keep forgetting this in higher ed?

This made me wonder how much of the recent coverage criticizing the skills of new graduates, and questioning whether they are prepared to thrive in the workplace, reflects who is being surveyed rather than what is actually happening. If samples lean disproportionately toward older employers and political independents, it is not surprising that the dominant narrative skews toward disappointment and decline.

I’ve seen this dynamic play out repeatedly in institutional decision-making. In workforce alignment projects, for example, colleges often rely on aggregated employer survey results to guide curriculum redesign. Those summaries tend to emphasize broad themes, “communication skills,” “adaptability,” “AI literacy.” But when the data are disaggregated by industry, firm size, or respondent role, the picture is far more fragmented. Those nuances rarely survive into strategy documents. Institutions end up designing programs around a simplified narrative that reflects who responded, not necessarily what students will encounter in the labor market.

A similar pattern appears in student support design. Institutions frequently build advising, retention, or engagement strategies based on surveys or focus groups that under represent key segments: online students, commuters, working adults, stop-outs, or caregivers. In other cases, programs are shaped primarily by staff perceptions of what students need. All of these perspectives matter. But each represents only one slice of a much larger and more complicated picture. When that slice becomes the whole, blind spots become baked into institutional design.

This is why findings from surveys and other data-gathering exercises need to be questioned more rigorously. So much depends on whom you ask, how you ask, and whose voices end up dominating the results. The patterns are often far less obvious than headline numbers suggest.

Higher education repeatedly builds policy and strategy on fragile evidence. The problem is not that surveys are useless. It is that we too often treat them as settled truth in environments where the stakes are enormous. More data will not solve this. What institutions need instead is greater interpretive discipline: the capacity to parse evidence carefully, understand its limits, and use it to inform, rather than dictate , policy and practice.

If you enjoyed this post or found it valuable, please forward it to everyone you know, and even some people you don’t!

Thanks for being a subscriber.