- On Student Success

- Posts

- The other transfer two-step

The other transfer two-step

Faculty discretion and document demands as hidden barriers to credit transfer

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

Recently at an EdTech-adjacent conference, I spoke with several early-career sales associates from companies building credit-transfer technologies. Though they worked for different firms and came from different states, they shared more than a sector: each was fired up by a uniformly awful personal experience trying to transfer credits as a student.

Setting aside the tech angle, this story is all too common. Every year, hundreds of thousands of U.S. students transfer between institutions, especially from community colleges to four-year universities in pursuit of a bachelor’s degree. Yet the process remains painful and error-prone, undermining student success. We know many of the culprits: too few advisors, messy data, and confusing requirements for students to navigate.

A new MDRC report adds another wrinkle: the pivotal role of faculty and document access. In mixed-methods research across three University of Texas system institutions, MDRC found that faculty often shape—and sometimes limit—credit transfer by requiring additional evidence of course equivalency, documentation that students frequently struggle to produce.

These dynamics matter. Most “best practices” overlook faculty discretion and the documentation burden. Until institutions address how faculty roles, standards, and evidence requirements operate within the transfer process, meaningful improvement is unlikely.

The scale of the problem

According to the Transfer Enrollment and Pathways report from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, transfer enrollment rose 4.4% (+50,600 students) in fall 2024 and is up 7.9% since 2020.

“Transfer” isn’t monolithic. Students move laterally (e.g., two-year to two-year or four-year to four-year) and vertically. The most familiar pattern is from community colleges (two-year) to four-year institutions. Last fall, 490,000 students made that move, an increase of 3.1% from 2023 to 2024. While the Aspen Institute notes that ~80% of community college students aspire to earn a bachelor’s degree, only 31% transfer to a four-year institution, and just 14% complete a bachelor’s within six years.

A key contributor to this gap is the difficulty of credit transfer, which is really a two-step process:

getting credits accepted by the receiving institution, and

getting them applied to degree or major requirements.

Research has documented multiple pain points; messy data, transcript delays, and too few advisors. Several states (e.g., Texas and North Carolina) have implemented articulation agreements to streamline credit transfer; these have generally helped, though in some cases they can complicate matters.

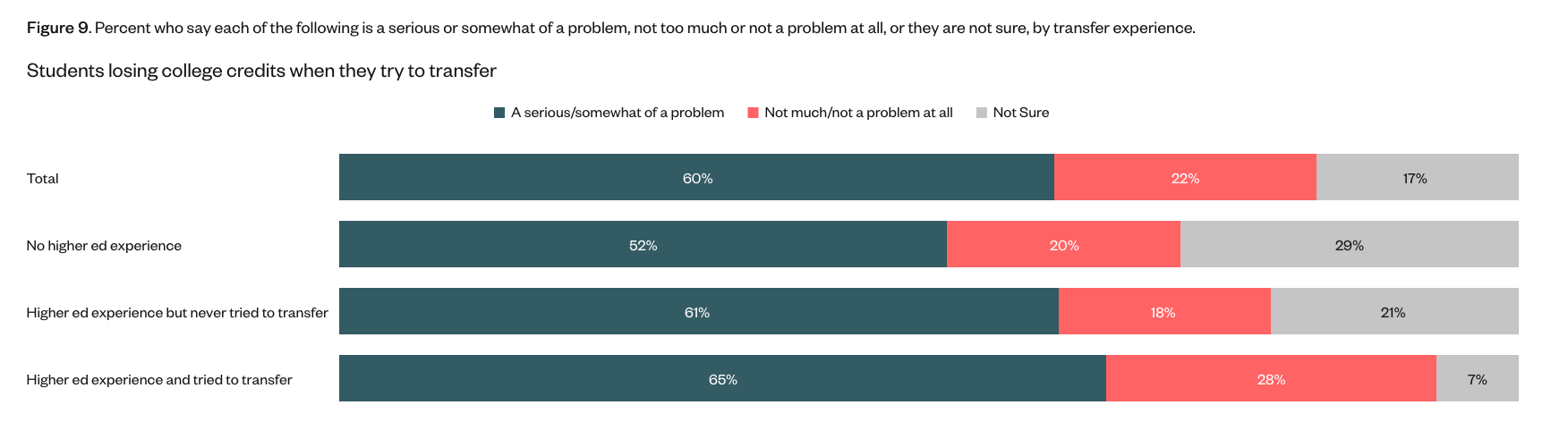

As Public Agenda research showed earlier this year, students experience intense frustration, often taking extra credits and spending more time and money to finish.

What’s often missing from the discussion is the role of faculty. A new MDRC report addresses that gap. Using a mixed-methods approach, combining data analysis with interviews of students, faculty, and staff at three regional University of Texas institutions, the study paints a more nuanced picture of how faculty decision-making influences whether credits are not only accepted but actually applied toward the degree.

The report examined credit transfer at the University of Texas at Arlington, the University of Texas at El Paso, and the University of Texas at Tyler. It confirms what students across the country already know: transferring credits from community colleges to four-year institutions is anything but straightforward.

The numbers are stark. At some institutions, over 40% of transferred credits never applied to degree requirements. In other words, colleges may “accept” transfer credits, but far fewer actually count toward the degree. At UT Arlington, for instance, 94% of credits were accepted for transfer, yet across the institutions an average of 42% of those accepted credits did not apply to a student’s degree.

Some familiar culprits emerge. The data itself is messy. Institutions vary widely in what they track about transfer; some can report how many credits arrive, but not how many are ultimately applied. Without consistent information, it’s nearly impossible to diagnose where students get lost.

The report also highlights two related, and less frequently discussed barriers that slow transfer: faculty discretion and document access. Faculty often serve as final gatekeepers of what counts. Sometimes that discretion helps students, overriding earlier decisions or approving exceptions. Other times it works against them, with courses rejected over what can feel like minor technicalities, especially when students can’t readily produce detailed syllabi or other documentation.

At one institution, for example, a faculty member described disagreeing with a colleague who denied a transfer because a single topic wasn’t listed in the sending institution’s catalog description, underscoring how subjective standards and limited documentation can derail credit application.

Another chair in [a department at the institution] rejected it because it left out one clause. They said, “Well, we cover these 10 subjects in our course, and I don’t see that it was covered there; therefore, we reject it.” And I thought, well, that’s really stupid, because course descriptions that are in the catalog are frequently ancient. They don’t have a lot to do with what faculty are actually doing. It’s more or less kind of a guideline.

There is often reluctance among faculty to standardize course equivalencies, even when doing so would make credit transfer more efficient and predictable. Faculty in particular resist creating “set-and-forget” rules for accepting certain classes.

Something that I think needs to get to the heart of some of this discussion [is] the once-and-always transfer pattern… I get we’re trying to save labor and make this faster for students, but in some ways, it’s really dangerous to go about setting up transfer that way.

In the four-year institutions MDRC studied, skepticism about the quality of community college learning is common. Department chairs and faculty often questioned the rigor and adequacy of community college coursework, even though institutional data show many transfer students perform well after moving to four-year schools. In fact, 41 percent increased their GPA in their first semester after transfer. In my experience, this skepticism extends beyond the two-year/four-year divide: faculty can be doubtful of quality even from similar institutions—or those in the same university system, in a kind of “not-made-here” bias.

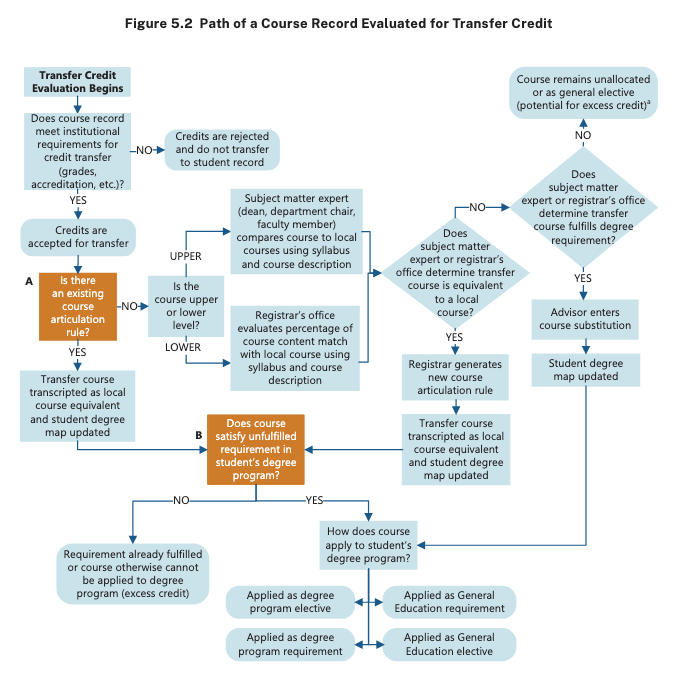

The net result is a labyrinthine credit-transfer process. Evaluations frequently involve multiple offices, faculty, and advisors, with information passed back and forth in a bureaucratic relay. At one institution, the average evaluation time was 15 weeks, during which students and advisors had little clarity about which courses to take next. MDRC’s flow chart underscores just how complex the process can be.

Compounding the delays is the second step in the transfer process: proving course equivalency. Students are often required to supply detailed evidence—course descriptions, syllabi, even assignments—introducing yet another hurdle that slows or blocks the application of credits to degree requirements.

reviewers conducting an evaluation require detailed course information and materials from the relevant semester including the course name and catalog description and a sufficient syllabus (with details about the required texts, instructional approaches, and assessment methods, for example). While course descriptions can often be found online, faculty members reported that they alone do not provide sufficient information on which to base a review. Several faculty members also noted that the course syllabi they receive—when they receive them—are also often inadequate, and supplemental materials (such as graded assignments and content from course learning management systems) are required. Importantly, this documentation gap often results in an additional burden on students to provide supplemental materials and prolongs the transfer credit evaluation process. ‘Some of these syllabi are just really, really minimal,’ a faculty member said. ‘And so, then we go back and forth with the student to ask them to submit… something supplemental to make up for the fact that the syllabus had nothing in it.’” Add the process reality: these handoffs commonly stretch timelines—one institution averaged 15 weeks per evaluation

While evidence matters, the burden placed on students is heavy, and much of it is outside their control. Syllabi may be incomplete or nonexistent. Accessing past course materials is unrealistic: students rarely keep syllabi or assignments during the course, let alone months or years later. They also can’t log back into a previous institution’s LMS, even if the course were still “live,” which it almost never is.

How do we fix this?

The report recommends addressing these problems by means of governance and making course information more easily accessible.

Standardize course record governance. As transfer courses are primarily evaluated based on course descriptions and syllabi, higher education systems and institutions must develop and implement templates and standards for these documents to ensure syllabi provide the information necessary for transfer credit decisions. Similarly, confirming that all syllabi are publicly available online (on an institutional webpage or platforms that host course information for multiple institutions, for example) can make transfer credit evaluation and course- to-course articulation efforts more efficient

I think the call for standardized templates for course documents is laudable but unlikely to work in practice. Even requiring a syllabus can be an uphill battle; some institutions still don’t mandate them, and imposing a set format is often contentious.

A more feasible step is to make syllabi publicly and persistently available, and to provide students with ongoing access to their assignments—or at least clear descriptions of what was required.

Finally, while we all value rigor and evidence-based decisions, institutions should develop clear guidelines and work with faculty to address biases against certain types of institutions and to define what constitutes sufficient coverage and proof.

Parting thoughts

Complexity is not an excuse for paralysis. Start with what’s doable: publish syllabi, clarify faculty standards, streamline cross-office workflows, and track where credits stall. None of these fixes solves everything, but together they shorten time-to-degree and reduce student cost—measurable wins worth pursuing now.

The main On Student Success newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.