- On Student Success

- Posts

- This Week in Student Success

This Week in Student Success

Ignoring the important bits

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

Late fall conference season is about to begin in earnest. I’ll be at OLC Accelerate in Orlando, OEB Global in Berlin, and CNI in Washington, D.C. If you’ll be at any of those and would like to grab a coffee and chat, let me know, I’d be delighted.

But first, what happened this week in student success?

Holistic food for success

CCCSE, the group behind the Community College Survey of Student Engagement (CCSSE) and other insights, has published a report on fostering a culture of caring in community colleges. I see this as a critical issue and was eager to dive in. The report synthesizes findings from CCCSE’s other surveys to examine the holistic supports colleges provide to students.

Students need multiple types of support that are provided systemically, intentionally, and consistently throughout their college experience. Students who report that their college provides this rich fabric of support—this culture of caring—have higher levels of engagement and success.

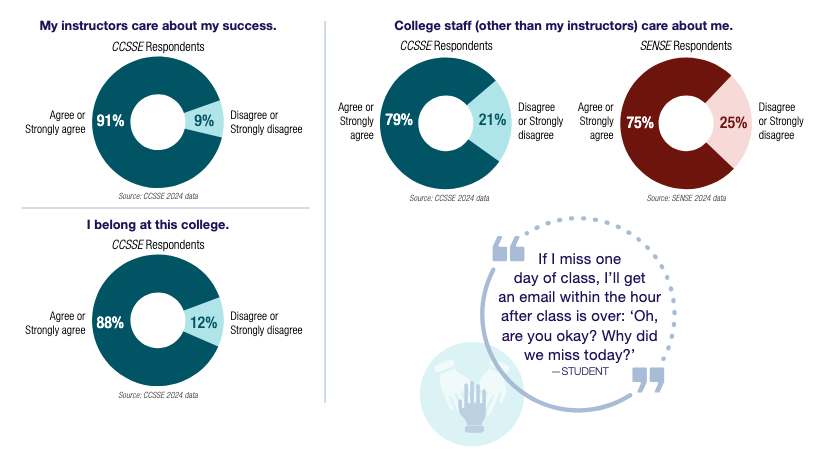

Data from the 2024 Community College Survey of Student Engagement (CCSSE) and Survey of Entering Student Engagement (SENSE) illustrate the elements and impacts of a culture of caring.

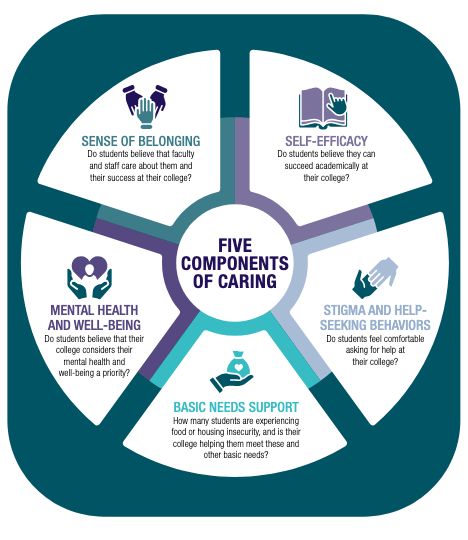

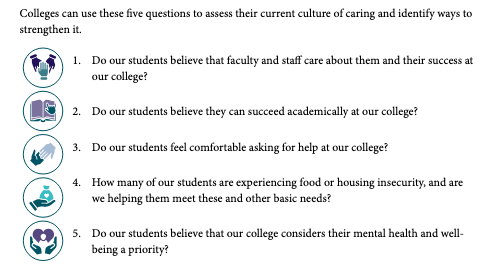

They note that colleges foster a culture of caring in many different ways, and they use a graphic to highlight several key components.

Probably because the authors were repurposing data from CCSSE and SENSE, they didn’t cover all of these issues, and certainly not in a systematic way. (Also, report writers, please: can we have titles and figure numbers in reports?). But I want to focus on three specific issues.

Trust

I was struck by the substantially greater trust students reported in instructors compared with staff. That feels somewhat counterintuitive, and I’d love to understand it better.

Engagement

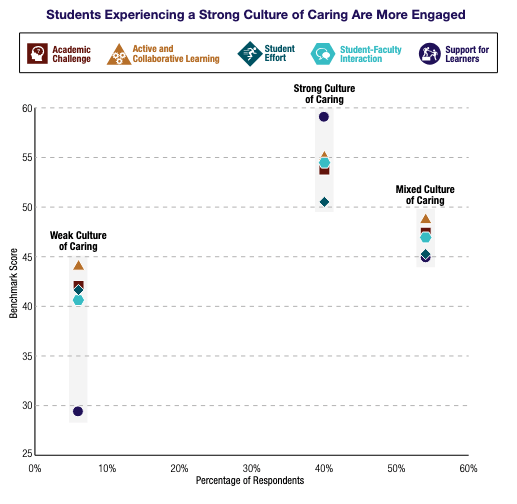

The authors divided students into three groups based on the strength of the culture of caring they experienced at their institutions. They don’t fully explain in the report how this grouping was done, but I assume it was based on some version of these measures.

They then mapped strength of the culture of caring to student engagement.

To assess the relationship between a culture of caring and engagement, we divided student respondents into three groups based on the level of caring they reported experiencing at their college. Students in the Strong Culture of Caring group are the most engaged. Students in the Weak Culture of Caring group are the least engaged. Most respondents fall in the Mixed Culture of Caring group and have engagement levels between the students in the strong and weak groups

Stigma

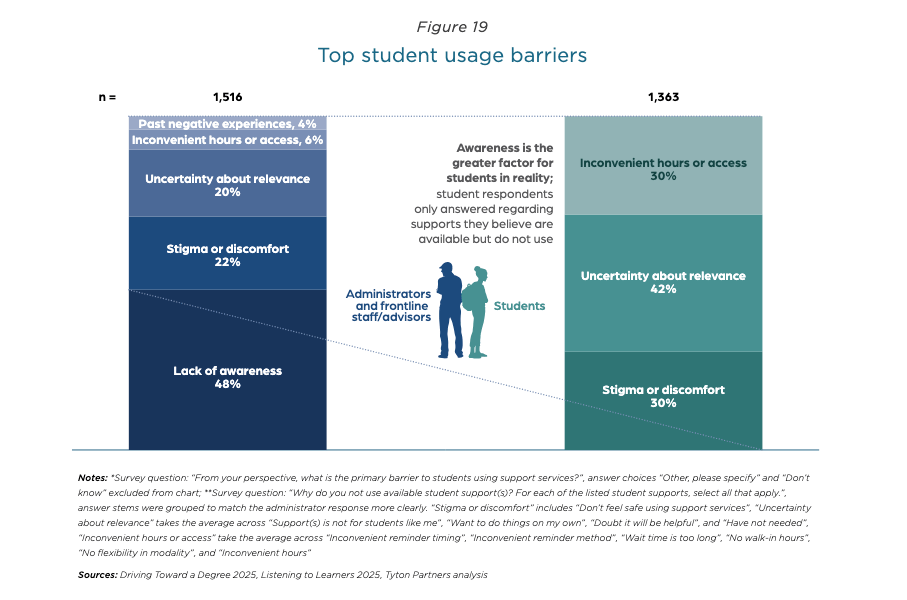

Given the authors’ identification of stigma and help-seeking behaviors in their Five Components of Caring, I was eager to see more on this, especially in light of findings from Tyton’s recent Driving Toward a Degree report. Even when students are aware of a support service, there is often significant stigma attached to using it. And Tyton’s survey focused mostly on conventional academic supports—advising, career services, etc.rather than more holistic supports such as housing, food security, and the like, which makes the stigma more surprising.

Isn’t that image title and figure number fantastic?

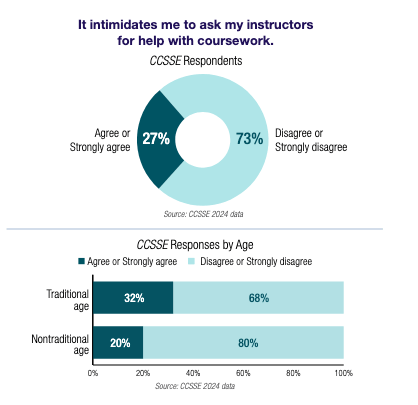

Unfortunately, the CCCSE report offered little coverage of stigma, apart from a single question about whether students felt intimidated asking for help with classwork, which isn’t really even stigma.

The limited attention to stigma surrounding other types of support is unfortunate, and not just because of my own disappointment. This is a critical issue we need to understand if we want to ensure students actually access the support they need.

I cant imagine why some people get paid more than others

I’ve long been interested in the transition from higher education to the workplace, and how both a student’s educational experience and that transition shape long-term success. A new NBER paper by Judith Scott-Clayton, Veronica Minaya, C. J. Libassi, and Joshua K. R. Thomas tackles exactly that question. It offers strong insights and makes a compelling case that the first transition into the workforce is a powerful determinant of post graduation outcomes, more so than demographics or college pedigree. Yet, ultimately, it left me scratching my head.

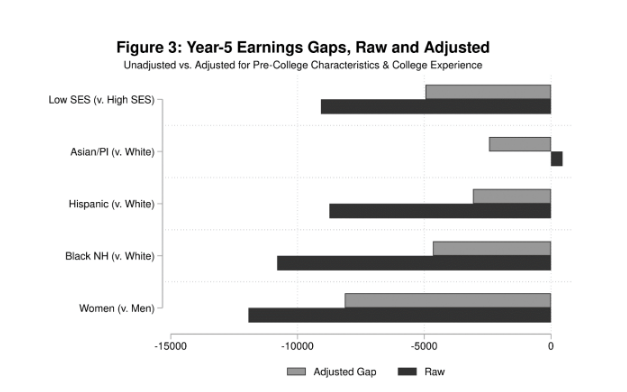

The paper examines why low-income graduates continue to earn substantially less than their higher-income peers, even after controlling for college quality, major, GPA, and demographics. Using administrative data from a large urban public university system linked with state labor-market records, the authors focus on the “first-job transition” as a neglected but powerful contributor to long-term inequality.

They find that:

First-job characteristics, such as firm size, industry–major match, and starting salary, strongly predict earnings five years after graduation.

Holding everything else constant, first-job salary and firm context (size, sector, salary structure etc) are major predictors of later earnings.

Low-income students are more likely to start in lower-paying firms and industries and to experience greater instability early in their careers.

A core part of their argument is reframing “undermatching,” a term usually applied to students attending less selective colleges, as an early labor-market phenomenon. Lower-SES graduates, constrained by financial pressures or limited networks, tend to “undermatch” into first jobs that offer weaker long-term payoffs, smaller firms, or poorer industry–major alignment.

The authors explain that the first job is a mediator that embeds preexisting inequalities into later career trajectories. Differences in financial resources, access to information, and job-search timing, rather than ability, drive much of this divergence.

But here’s where my perplexity comes in: the authors stop short of unpacking why this undermatching happens. They identify the pattern but don’t explore the mechanisms behind it. They argue that.

Some puzzles and open questions remain, however. If lower SES graduates are matching to lower-paying firms and earning lower wages than their college, major, GPA, and other pre- graduation characteristics would predict, what is driving these differences?

I believe they provided a good part of the answer to that question themselves. In the following chart.

Hype first

This made me chuckle, especially given headlines like these

The normative tendency in student success

For reasons, I’m currently reading a lot about leadership. That said, I’m enjoying Jeffrey Pfeffer’s Leadership BS: Fixing Workplaces and Careers One Truth at a Time. One comment in particular really struck a chord with me.

The leadership industry is so obsessively focused on the normative—what leaders should do and how things ought to be—that it has largely ignored asking the fundamental question of what actually is true and going on and why. Unless and until leaders are measured for what they really do and for actual workplace conditions, and until these leaders are held accountable for improving both their own behavior and, as a consequence, workplace outcomes, nothing will change.

I think something similar happens with student success, particularly when it comes to student success interventions. We see plenty of coverage of the problems: low retention rates, the forty-plus million adults in the U.S. with some college but no degree. But when it comes to solutions, it’s rare to find honest discussions of lessons learned or failures. We tend to fixate on what should be, and avoid talking about what didn’t work—or, heaven forbid, what went horribly and spectacularly wrong.

I wrote about a version of this a couple of years ago in On EdTech, in a piece acalled Success P-rn in EdTech (I’ll spare the full word so this doesn’t trigger spam filters). It’s a real problem, and one we need to get over if we’re serious about making progress on student success.

Great chart, thin playbook

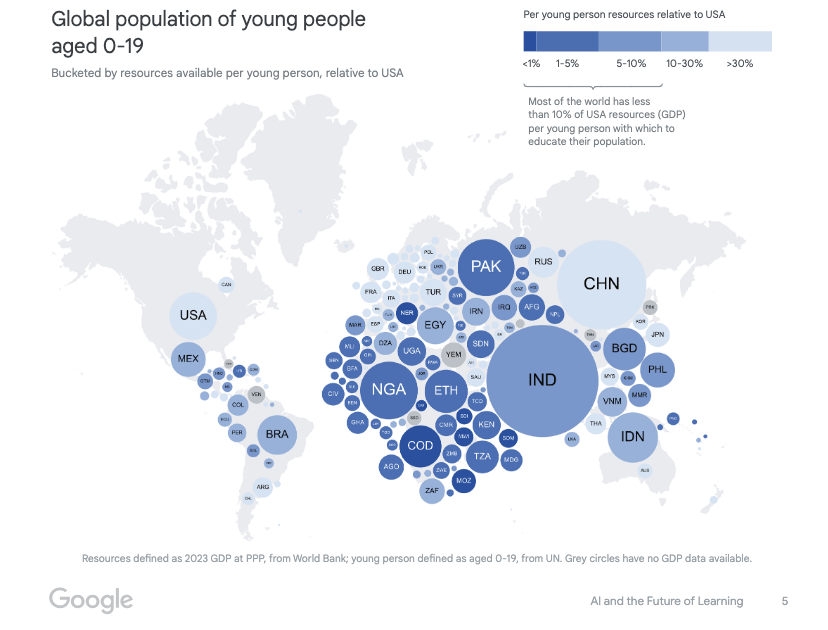

Google has a new paper on learning and AI that’s notable for focusing more on learning than on AI. The problem is that its treatment of learning is fairly generic and doesn’t offer concrete answers, or even especially interesting discussions, about how to harness AI as a learning tool while addressing obvious issues like shortcut-seeking or cheating.

What I did really like, though, was their chart showing where young people live and their access to resources relative to the U.S. It vividly underscores how global conversations about student success can’t be grounded in U.S.-centric assumptions.

Musical coda

This one hits home today. City Hall, by Vienna Teng.

The main On Student Success newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.