- On Student Success

- Posts

- This Week in Student Success

This Week in Student Success

What's working, what's not, and why cynicism helps no one

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

I’m not sure what’s worse, the fact that the weeks seem to fly by faster and faster, or that my local Costco is already winding down its Christmas display after putting it up in early September.

So, what happened this week in student success?

Silver buckshot

It came out a few weeks ago (see my point about the weeks speeding by), but Inside Higher Ed’s annual Student Voice survey is a useful reminder that students’ challenges are varied, so there’s unlikely to be a single solution to student success.

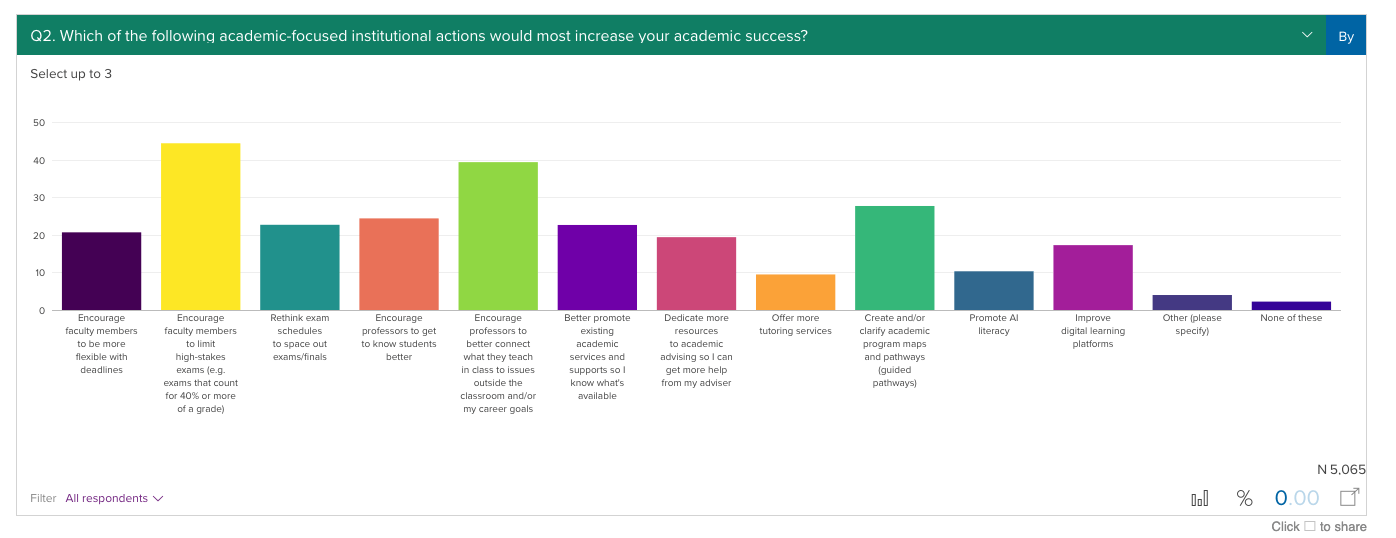

In response to a question about what actions would improve their academic success, more than 5,000 students offered a wide range of suggestions.

Reducing high-stakes assessments (where a single exam counts for 40% or more of the final grade), connecting coursework to real-world problems, and providing more guided pathways garnered the most support. The broader takeaway: when it comes to student success, there’s rarely a silver bullet, the challenge usually calls for silver buckshot (a phrase I stole from Dawn Medley from SUNY Stony Brook).

That doesn’t mean initiatives should be launched in a buckshot-like manner. Too often we see too many programs addressing too many issues, implemented without evaluation to determine what’s moving the needle and what isn’t. It’s something I’m thinking about a lot and will be writing more about soon.

Of cynicism, cheap shots, and Pong-gate

I recently reread The Data Detective by Tim Harford. In the introduction, Harford explains why he dislikes Darrell Huff’s well-known 1954 book How to Lie with Statistics. Huff’s book is witty and uses humor to skewer statistical claims of all kinds. But in doing so, it also casts suspicion on statistics and evidence themselves. Harford describes it as “junk food.”

Part of Harford’s distaste, no doubt, comes from the fact that Huff later took money from the tobacco industry to mock and sow doubt about emerging research linking smoking to cancer and other diseases.

The larger point Harford makes, though, is that it’s easy to become overly cynical about data, to dismiss its use instinctively and out of hand. Skepticism is healthy; cynicism is corrosive. Too often today, we see doubt being peddled as a product, used to undermine trust in experts and in people who have spent entire careers studying, practicing, and deeply understanding their fields.

As Harford writes.

I worry about a world in which many people will believe anything, but I worry far more about one in which people believe nothing beyond their own preconceptions.

Too often these cynical preconceptions are recycled as hard positions and hot takes, devoid of evidence but endlessly repeated because they are provocative and poke at more expert knowledge

I am writing about this because this past week at the annual Gartner Symposium the main Gartner keynote included a claim about the eroding value of a college degree. Tim Chester, in his newsletter, describes this claim far more generously than I am about to. Gartner announced that.

AI will quickly erode the ROI for a college education, and by 2030 it will invert the ROI dynamic entirely.

From other attendees, I heard that this claim was accompanied by a graphic of beer pong, and no actual supporting data. Apparently, Gartner walked the claim back a little the next day, but the fact that it was made at all is telling.

To me, this is a textbook example of the cynicism Harford warns about. The data on the ROI of higher education is extensive. Does a degree pay off for every student, every time? Of course not. Does higher education need to make changes, why yes it does and that is why I and others write about that almost daily. But across the board, a college education is strongly correlated with higher earnings, lower unemployment, and even longer life expectancy.

So to declare, especially in a venue like the Gartner Symposium, that a college degree will soon have no ROI is not just misleading, it’s a cynical swipe at expertise itself. It’s also, frankly, a cheap shot that undermines Gartner’s own brand. As someone else pointed out to me.

That’s an interesting phrase for an individual provocateur to use to grab attention and make a point—but pretty horrible branding for a group that claims to help you do sober analysis and make sense of complex situations.

I spent over seven years at Gartner and still have enormous respect for my excellent former colleagues on the education team, whom I’d bet dollars to donuts were not consulted about the claim of declining ROI. They, and higher education itself, deserve better.

A global lens on transfer transitions

Many years ago, when I arrived at the University of Minnesota (Go Gophers!) as a new international graduate student, one of the required orientation sessions was a daylong workshop on how to dress for winter. Two staff members from the international student office brought suitcases full of their own clothing and taught us the importance of layering and keeping extremities warm, holding up long underwear and noting that while we might laugh now, by February we’d be grateful to be wriggling into a pair. They also shared tips on where to buy quality gear inexpensively.

Unlike many orientations I’ve attended, that one was genuinely valuable. And it seems Minnesota is still pushing the envelope with innovative offerings. An article this week described a course at the Carlson School of Management designed specifically for transfer students. In the course, students use design thinking to reflect on and contextualize their college experience and career plans in a global context.

The “Design Your Life in a Global Context” course encourages transfer students to apply design-thinking principles to their college career and beyond and organizes a short study-abroad trip led by a faculty member. The experience, mostly paid for by the institution, breaks down barriers to the students’ participation and aims to boost their feelings of belonging at the university.

Toward the end of the course, students spend ten days in Japan. The costs are heavily subsidized by the university with support from the Carlson family foundation.

First of all, where can I sign up?

More seriously, I love the idea of a design-thinking or “design your life” course, especially for transfer students, to encourage more intentional planning. I know some career offices do something similar, but it’s great to see it in the regular curriculum. I’d also love to see it expand beyond the business school.

Early beginnings

Staying with the theme of transfer and transitions, a new report from the Public Policy Institute of California confirms what many on the front lines of student success have long suspected: a student’s first year is critical.

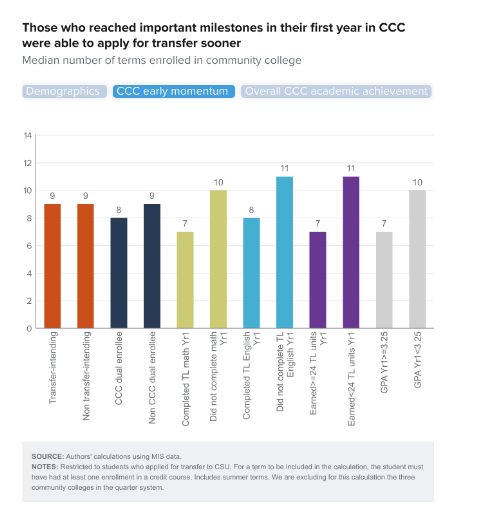

Using data from the California State University and California Community College systems, the report shows that the speed of transfer from community college to a CSU four-year institution varies considerably by factors such as ethnicity, age, and Pell Grant status. Students who complete key milestones early in their community-college careers, however, tend to transfer much sooner.

We find that the typical CSU applicant spends nine terms enrolled in the community college system prior to applying to CSU [snip] However, some applicants are able to apply for transfer sooner, especially those who exhibited early momentum [snip]. For example, the typical student who successfully completed transfer-level math in their first year was able to apply to CSU after seven terms while the typical student who did not complete transfer-level math was not able to apply until attending for 10 terms. Other first-year outcomes (completing transfer-level English, or earning 24+ transferable units, and higher GPAs) are also correlated with more efficient transfer

This is great news, and points toward potential student success solutions aimed at guiding students to do those required benchmarks early.

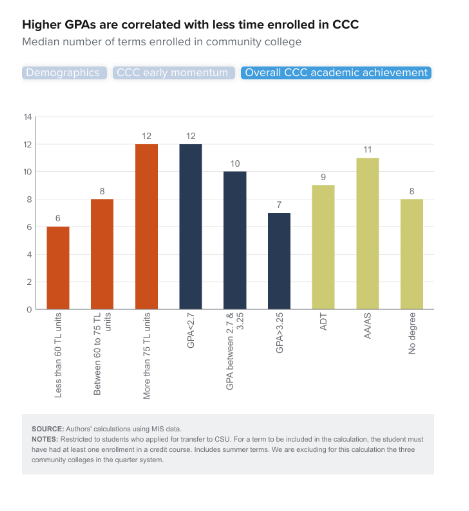

However, I am concerned about the fact that the speed to graduation is so heavily correlated with GPA. Students with a GPA below 2.7 were enrolled for 12 terms before transferring while students with a GPA over 3.25 were enrolled for only 7 terms before being able to make the move to the CSU.

This makes me worry that we’re simply seeing strong, motivated students doing better, and the report doesn’t convince me that it controlled for that. I’d love to see some cross-tabs or an analysis of students with risk indicators, i.e., low GPA or Pell grant status, transferring sooner than similarly situated peers because they hit those milestones early.

The other type of investing in student success

Among the publications I regularly follow on EdTech funding and investment, two favorites are Matt Tower’s The EdSheet and The Brighteye Bulletin. It’s not often that I see funding announcements for vendors squarely focused on student success, but lately there have been more:

Outsmart led by several former Duolingo executives and aiming to make “the best parts of higher education available to many more people in ways that feel relevant to how the world actually works today” raised $25 million, led by Khosla Ventures, Lightspeed, Abstract, Reach, and Latitud.

Knack, a student tutoring platform, closed a Series B led by New Markets Venture Partners.

EdSights, a student-voice platform that uses chatbots to gather input and bolster student success, received a strategic investment from JMI Equity.

Musical coda

Because I was talking about Minnesota.

The main On Student Success newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.