- On Student Success

- Posts

- This Week in Student Success

This Week in Student Success

Always questioning assumptions

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

The beginnings of years are such complex times: the excitement of a new beginning, the disappointment of having achieved much less over the break than anticipated. But what is happening this week in student success?

Where the boys aren’t

The American Institute for Boys & Men published a fascinating post on the achievement gap between men and women in college and university attendance. Contrary to those who might argue that this is a nothing-burger, I think this is an important issue that deserves close attention—and action—for several reasons.

First, men make up roughly half the population. If we ignore their under-attendance in tertiary education, it will eventually affect enrollment in an already constrained environment.

Second, if we believe in the societal and economic value of tertiary education (which I do), then having one group systematically under-participate is not a good thing.

Third, men’s under-participation in higher education may ultimately be dangerous for women as well. There is a risk that higher education becomes “feminized” and associated primarily with women’s participation—and therefore less valued. We have seen versions of this dynamic in parts of the world and in certain professions; for example, as more women entered medicine, the prestige (and, in some cases, salaries) associated with the profession declined.

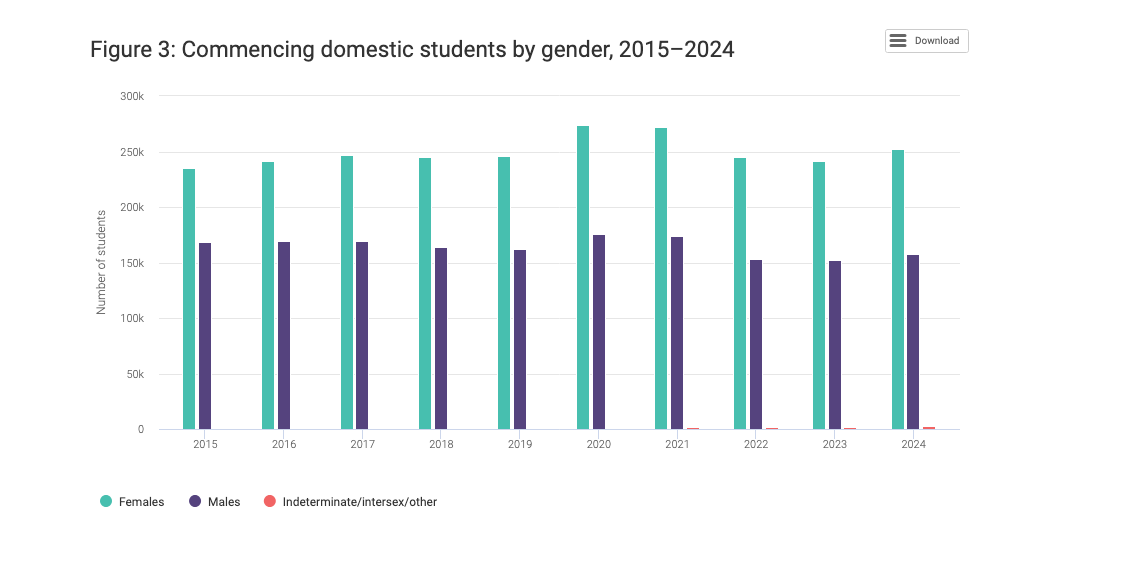

As a recent report from Australia highlights, this is not just a US phenomenon.

Over the past decade, the gender make-up of commencing domestic students has changed further, with the number of female domestic commencing students increasing 7.3 per cent from 2015 – 2024, while the number of male domestic commencing students has decreased by 5.9 per cent. These changes have resulted in females increasing to 62 per cent of the commencing domestic cohort in 2024, up from 58 per cent in 2015, while the male share of commencing domestic students decreased from 42 per cent in 2015 to 38 per cent in 2024.

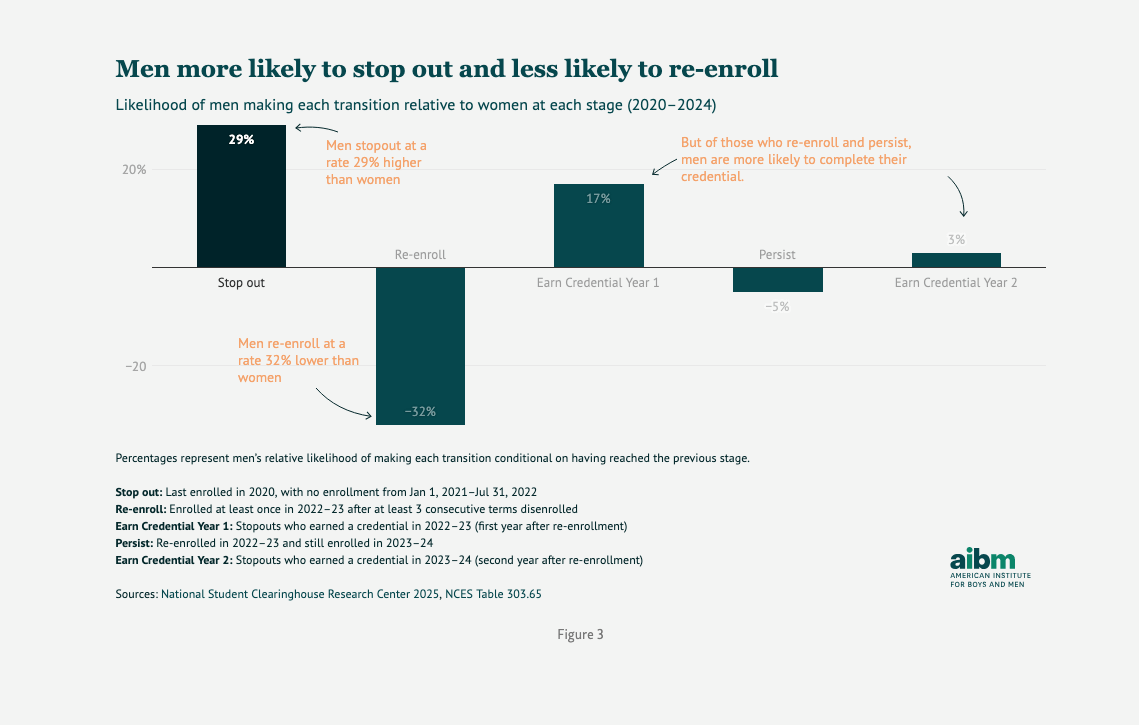

Where the AIBM post is especially helpful is in drawing attention to the fact that the issue is not only that women are participating in higher education at higher rates, but also that men are stopping out, meaning they are not being retained or persisting, at higher rates as well.

In fall 2020, men made up 41% of undergraduates—about 3.3 million fewer than women. But men stop out at higher rates: they accounted for 48% of recent stopouts in 2022-23 and 51% of stopouts overall, a gap equal to roughly 700,000 additional men who have left college without a credential. Men are also less likely to return to college and make up only 42% of re-enrollees.

What the AIBM post implicitly makes clear is that we need to focus on two distinct, if related, issues:

Why men are participating in higher education at lower rates.

Why they are stopping out at higher rates and re-enrolling less often.

Catching up

While spending some time on the Australian Higher Education Statistics site, I did notice some good news about success rates for domestic students in Australia. Their success rates have now essentially caught up with those of international students, who tend to be high achieving.

They define success as.

The success rate measures the proportion of units of study passed [snip] from all units of study attempted.

The folks at Higher Education Statistics attribute the equaling of success rates to a mix of positive actions and policy moves.

The recent focus on equity and student support across a range of measures may be contributing to achieving this outcome. Engagement with higher education providers by the Department supports this, with many citing both academic and non-academic supports helping to improve student outcomes.

Efforts by government and higher education providers to minimise non-genuine overseas students is likely to have contributed to the increased success rate of the overseas cohort.

What you ask for, versus what you really want

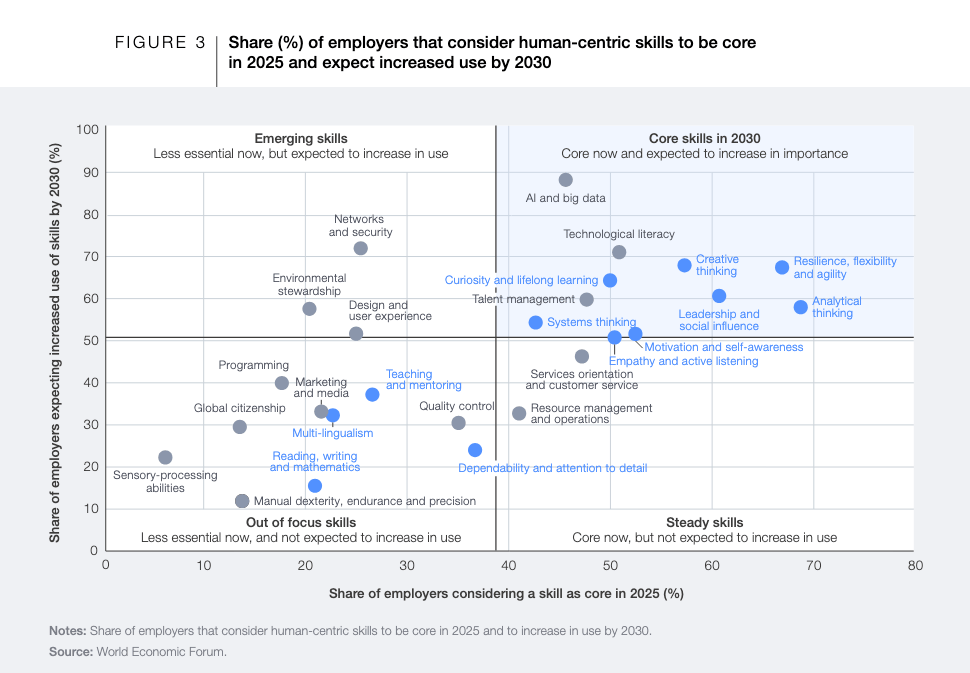

In a recent white paper on skills for the new economy, the World Economic Forum (WEF) identified skills that employers believe are growing in importance, as well as those perceived to be in decline.n a recent white paper on skills for the new economy, the World Economic Forum WEF identified skills that employers believe to be increasing importance and those that are perceived to be declining.

Analytical and systems thinking, creativity, resilience, motivation and self- awareness, as well as curiosity and lifelong learning are not only core today, but will remain critical over the next five years. By contrast, skills such as dependability and attention to detail; teaching and mentoring; multilingualism; and reading, writing and mathematics are expected to plateau, increasingly viewed as assumed or supported by technology.

Apart from the vagueness and subjectivity of some of these concepts—what model of leadership do they mean, what is systems thinking, and how are either of those evidenced?—it is hard to argue with many of them.

But as Stowe Boyd points out in Work Futures, quoting research by Jana Werner and Phil Le-Brun, the skills and behaviors that employers say they want in employees and those they actually recognize and reward are often two very different things.

While 73% of executives recognized curiosity and imagination as critical, only 9% of employees felt their leaders supported those traits, such as by encouraging them to be curious and to explore new ideas.

This is of course not true of the data and charts I share with you

Imagine if student success paid this well

In an article ostensibly about early decision, The New York Times documented a tendency at a number of private universities to pay those running enrollment management eye-wateringly large salaries, by higher education standards, often in the high six figures and even into seven figures.

If you’re the gatekeeper at schools like these, where over a third of the students will pay full price — $400,000 or so over four years — you earn your keep by landing just a few more of them each year.

Miss your number, however, and the shortfall can cascade through four years of revenue shortages. You could also be out of a job.

Vice presidents of sales at high-performing organizations make the big bucks, and thousands of teenagers now sign up each year to say Chicago, Northeastern or Tulane is their true love always.

Shouldn’t that count for an awful lot?

In reply to a New York Times’ question about the compensation, one university spokesperson replied that.

For this role in particular, I think it’s important to know that the university’s revenue from student enrollment exceeds $2 billion annually.

I am all for people being paid well, but by that logic, shouldn’t student success professionals be paid more, given their role in retention and persistence—and the downstream impact both have on revenue?

But is that the right way to think about it? I would argue that it is not.

Still skeptical after all these experiments

One of the biggest questions I find myself grappling with in both the EdTech and student success spaces is the use of generative AI for tutoring. On the one hand, there is enormous potential in this technology and a substantial payoff if it works. On the other, there is a great deal of bogus speculation, the mere mention of Bloom’s two-sigma is enough to raise my blood pressure these days, alongside poorly designed research on the topic.

So I read with interest a recent Philippa Hardman post describing research conducted at the BCG Henderson Institute on using AI for tutoring in the flow of work. Drawing on that research, Hardman argues that learning in the flow of work may be not only possible, but actually superior to traditional classroom or LMS-based L&D.

In the experiment, mid-career professionals at BCG were tested on their understanding of problem framing. Some participants then received classroom-based training on the topic, while others received AI coaching (the exact form of which is unclear) while working on real tasks. The results were impressive.

After testing with 139 employees, three key findings emerged:

* An AI coach was able to teach complex skills to the same level as the expert instructor, but 23% faster overall.

* Learners who started with the lowest scores (i.e. who had the most to learn) saw 32% larger gains achieved with an AI coach when compared to peers who learned in in the classroom.

* After just one interaction, 53% of learners rated the AI coach higher than the human instructor, for three reasons:

— its ability to offer “judgement free practice”

— better “learning-job’-fit”

— more tailored and personalised feedback

TLDR: The evidence suggests that “learning in the flow of work” is not only feasible as a result of gen AI—it also show potential to be more scalable, more equitable and more efficient than traditional classroom/LMS-centred models.

I am less impressed and optimistic than Dr. Phil. Without knowing more I think claims of AI superiority are a tad premature, for the following reasons.

After testing on one skill, it seems a stretch to extrapolate the results to all workplace learning. How would different kinds of roles respond and would different types of topics make a difference.

We know little about how the experiment and the tutoring was structured. It is thus impossible to know how much of the differences in understanding were due to AI and how much on careful instructional and organizational design.

Finally, a growing concern in the learning literature is on skill atrophy as cognition and struggling with concepts is externalized to AI. The results of the AI assistance and tutoring could be short-lived or even harmful in the medium to longer term. This is not addressed.

I do still believe that AI tutoring has potential. But many of the studies and experiments on the topic appear to be jumping to premature conclusions.

Musical codas

The Ndlovu Youth Choir from South Africa singing Bohemian Rhapsody in isiZulu. Somewhere Freddie Mercury is smiling and listening to it on repeat.

They also do an amazing Nessun Dorma.

The main On Student Success newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.