- On Student Success

- Posts

- This Week in Student Success

This Week in Student Success

The systems that matter

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

Apparently, it is research article week over here at On Student Success. But among the usual Greek-filled documents and dense regression tables, four studies in particular caught my attention, because together they tell a revealing story about what actually shapes student success.

They are about belonging, money, and AI.

What struck me in reading these studies is how little any of them point to “silver bullets.” Instead, they all point in the same direction: student success depends on whether institutions build reliable systems of support — social, financial, and instructional — and sustain them over time. In other words, whether students feel connected, whether they can afford to stay, and whether our newest tools are helping or distracting.

Belonging: A Signal, Not a Solution

At a gut level, most of us know that belonging matters for student success. A recent study by Shannon Brady and Maithreyi Gopalan provides strong national evidence that this intuition is correct.

They define belonging as.

Students’ sense of belonging—their perception of being included in their educational environment

Using data from more than 21,700 undergraduates who entered college in 2011–12, the authors show that students’ sense of belonging, measured in their first and third years, was positively associated with degree completion. A one-point increase on their five-point belonging scale corresponded to a 3.4 percentage-point increase in four-year completion and a 2.7-point increase in six-year completion.

Importantly, this is not just a freshman-year phenomenon. Changes in belonging after the first year also matter, suggesting that students’ ongoing experiences continue to shape their outcomes.

Among students who begin at 4-year colleges, change in belonging appears to matter independently of first-year belonging. Although the data are correlational and subject to nonresponse bias, this suggests that what happens after students’

first year can shape their feelings of belonging and later

outcomes.

Their findings apply at both four-year and two-year institutions, though they are less robust at the two-year level.

The study is careful and appropriately modest. But it also has limitations. Belonging is measured with a single self-reported item, which makes it hard to know what is really being captured. Is it social integration? Advising quality? Teaching effectiveness? Feeling valued? Probably some combination.

Belonging may also be a proxy for whether institutional systems are working. We know from other research that students with stronger belonging are more likely to use advising and support services. But this study cannot tell us whether belonging causes engagement, or engagement causes belonging.

The data are also dated. These students largely missed the pandemic, large-scale online expansion, today’s affordability crisis, and the rise of generative AI.

Still, the central lesson is important. Students’ subjective sense of being “part of the institution” is a meaningful indicator of persistence. But it does not mean that “making students feel welcome” is enough. More likely, belonging reflects whether institutions are functioning well for students. When systems work, students stay. When they don’t, they leave.

Belonging is a signal. It is rarely a lever by itself. This matters, because many institutional initiatives treat belonging as something to be “designed” through messaging and programming, rather than something that emerges when advising, teaching, and financial systems actually work.

A Bona Fide Emergency

If you read through the short list of institutions that have genuinely improved retention and completion, one pattern appears again and again: some form of emergency financial support.

A new report from Trellis Strategies shows why this matters.

In the Fall 2024 Student Financial Wellness Survey [snip], over half of all undergraduate respondents [snip] reported they would have trouble coming up with $500 in cash or credit in case of an emergency. This financial fragility was especially common among parenting students (70 percent) and first-generation students (67 percent).

Furthermore, over a quarter of SFWS respondents (28 percent) indicated they had run out of money six or more times in the past year. This represents a structural budget deficit where individuals’ finances are regularly in crisis with no opportunity

to get ahead. A lack of emergency fund means that any sudden expense—such as a car repair, medical bill, or technology issue—becomes an acute financial emergency.

Ultimately, these financial challenges can jeopardize a student’s ability to remain enrolled in higher education. In Trellis’ surveys of individuals with some college but no credential, 35 percent of respondents indicated finances as a primary reason for

stopping out.

During the pandemic, HEERF funding temporarily filled this gap, and emergency aid became widespread. But Trellis’s longitudinal data show that access has collapsed since federal funds ended.

The chart showing emergency aid receipt falling from roughly 44 percent in 2021 to around 5 percent in 2024 should be unsettling for anyone concerned with equity and completion.

Given what we know about student finances, this decline is not just unfortunate. It is dangerous. The danger is not simply the loss of federal funding. It is that many institutions have made no serious effort to replace it with permanent institutional resources, leaving students stranded.

The Most Accurate Chart I May Ever Have Shared

If you spend much time traveling for higher education work, you may recognize this immediately.

Patterns tend to repeat when systems don’t change.

AI as a Help Desk, Not a Professor

AI tutoring is one of the most important emerging issues in student success. In principle, it offers affordable, personalized, and scalable support. In practice, it is surrounded by hype.

A new in-press study provides a useful reality check.

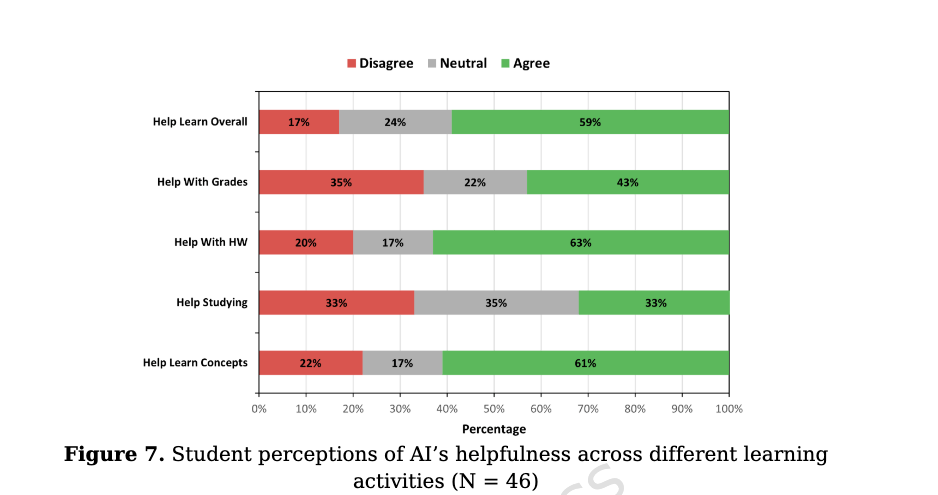

Researchers evaluated a course-embedded AI system in two engineering courses, tracking how 71 students used six tools: summaries, a chatbot, flashcards, quizzes, a coding sandbox, and syllabus help.

Students mostly used the system for low-stakes support: clarification, troubleshooting, and getting past blockages. They rated AI as far more convenient and easier to approach than instructors or TAs, but clearly inferior in instructional quality.

Despite that, students did find that the AI tools helped them learn.

Interestingly, some of the major barriers stopping students from making greater use of the tool were concerns that doing so would be cheating, or at least contrary to university policy. In surveys.

A majority (58%) reported concern about being accused of academic

misconduct when using AI, and 42% indicated they were uncertain or only

somewhat confident in identifying what constitutes a violation.

The authors’ recommendations are sensible. General university policies are not enough. Students need “permissive but bounded” guidance at the course level, with concrete examples of acceptable use.

The data indicate that generalized university policies are insufficient to alleviate student anxiety; instead, a shift toward 'permissive but bounded' course-level frameworks is required. Instructors should move beyond binary 'allowed/not allowed' statements in syllabi and instead provide explicit examples of permissible use cases, such as using AI for code debugging or concept summarization, while clearly defining the boundaries of academic misconduct. Furthermore, to mitigate the 'ethical dissonance' observed, institutions should prioritize AI literacy over

surveillance, shifting the focus from punishment to guiding students on how

to attribute and verify AI-generated content. By co-creating these guidelines

with students, who favored regulation over bans (Fig. 9), educators can foster

a culture of transparency that aligns with the professional ethical standards

of the engineering discipline

This is not a technology problem; it is a governance problem.

It’s Not AI Literacy. It’s Engagement.

An Italian study examined how students’ attitudes toward ChatGPT (as a representative generative AI chat tool), trust in it, engagement with it, and knowledge about it relate to critical thinking.

The key finding is simple and important.

What matters most is not how much students know about AI. It is how they use it.

Using validated instruments to measure attitudes, experience, trust, and knowledge about AI, as well as critical thinking, and path analysis grounded in Bandura, Kahneman, and cognitive load theory, the researchers found that engagement was the central variable. What mattered most was not what students knew about ChatGPT, but how actively they used it.

Students who trusted AI and felt positively about it were more likely to engage with it and build experience. But simple familiarity did little on its own. What predicted stronger reasoning skills was active, reflective engagement: questioning responses, exploring alternatives, and using the tool as a thinking partner rather than a shortcut. Students who engaged in this way not only performed better on reasoning tasks, but also developed more positive attitudes toward critical thinking itself. By contrast, passive use—accepting answers and copying text—had little benefit. In short, the study suggests that AI supports thinking only when pedagogy and course design encourage students to use it thoughtfully.

Ultimately, what this study suggests is that AI literacy by itself, in isolation, does very little for critical thinking. What matters is whether students are actively engaging with ideas through the tool. Passive familiarity doesn’t build thinking skills. Structured engagement does. And how AI use is structured by instructors is central to that.

Optimizing educational policies to systematically integrate AI-based

tools like ChatGPT into the curriculum requires a targeted approach that

actively promotes student engagement rather than merely fostering

passive consumption of information. Teachers play a crucial complementary role as partners in the educational process, interpreting and

guiding students’ learning paths in a thorough and contextualized

manner.

This places substantial new demands on instructors, many of whom are already stretched thin and receive little institutional support for this work. It puts pressure on them both to engage thoughtfully with AI themselves and to structure course content in ways that foster reflective engagement among students. But if AI literacy and critical thinking are our goals, this is work we cannot avoid.

Small Systems, Big Consequences

What struck me this week is how much student success depends on small, often invisible systems: emergency grants, advising relationships, assignment design, and policy clarity. When those systems work, students persist. When they fail, no amount of rhetoric can compensate.

For institutional leaders, none of this is especially mysterious. What is hard is sustaining investment in unglamorous infrastructure: emergency aid funds, faculty development, advising capacity, and policy work. These rarely produce quick wins. But over time, they shape outcomes far more than pilot projects or new platforms.

A Cool Thing I Came Across

Sticking with Italy, I love this concept.

Musical Coda

On Saturday, in the On EdTech newsletter, ChatGPT and I wrote a version of Bob Dylan’s The Times They Are a-Changin’, but about the impact of AI on search as it relates to online learning (as one does). That got me thinking about this song, one of my favorites.

The guitar malfunction is extra.

One of the small acts of kindness you could do for me, which would echo across the internet, would be to share this post with others who may find it useful and encourage them to subscribe.

Thanks for being a subscriber.