- On Student Success

- Posts

- This Week in Student Success

This Week in Student Success

Roads taken and not taken

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

I’m writing this from the meat grinder that is U.S. air travel, en route to Edinburgh (Scotland, not Indiana) for MoodleMoot Global 2025. If you’ll be there, say hello, I’d love to connect. But what happened this week in student success?

Random acts of dual enrollment

Dual enrollment, where high school students take college courses for credit while still in high school, has become a significant and growing part of higher education.

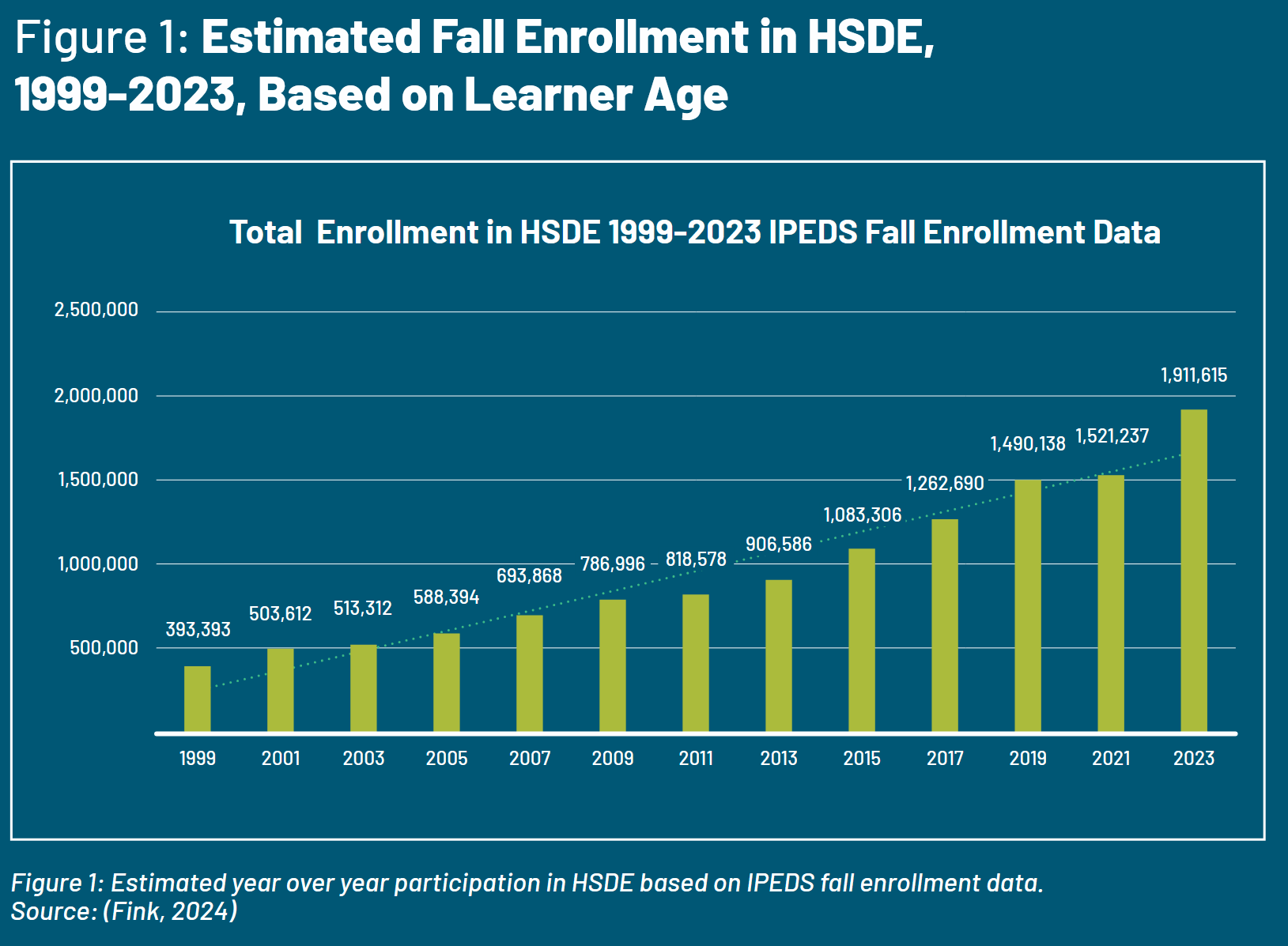

A new survey report from AACRAO (the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers) and NACEP (the National Alliance of Concurrent Enrollment Partnerships) sheds welcome light on this trend. The report is particularly strong in explaining how and why high school dual enrollment (HSDE) is expanding. Since AACRAO’s last survey in 2016, HSDE participation has grown by 15%, and 80% of institutions that offer HSDE report growth at their own campuses.

Impressive as it is, the growth data only hints at the scale of HSDE. Preliminary IPEDS data for 2022–2023 show that HSDE accounts for 12% of all undergraduate enrollments and a striking 21% of community college enrollments.

HSDE is positively associated with increased access and student success in higher education. Students who participate enroll in college immediately after high school at much higher rates than non-participants (81% vs. 70%), and they complete college credentials at substantially higher rates as well.

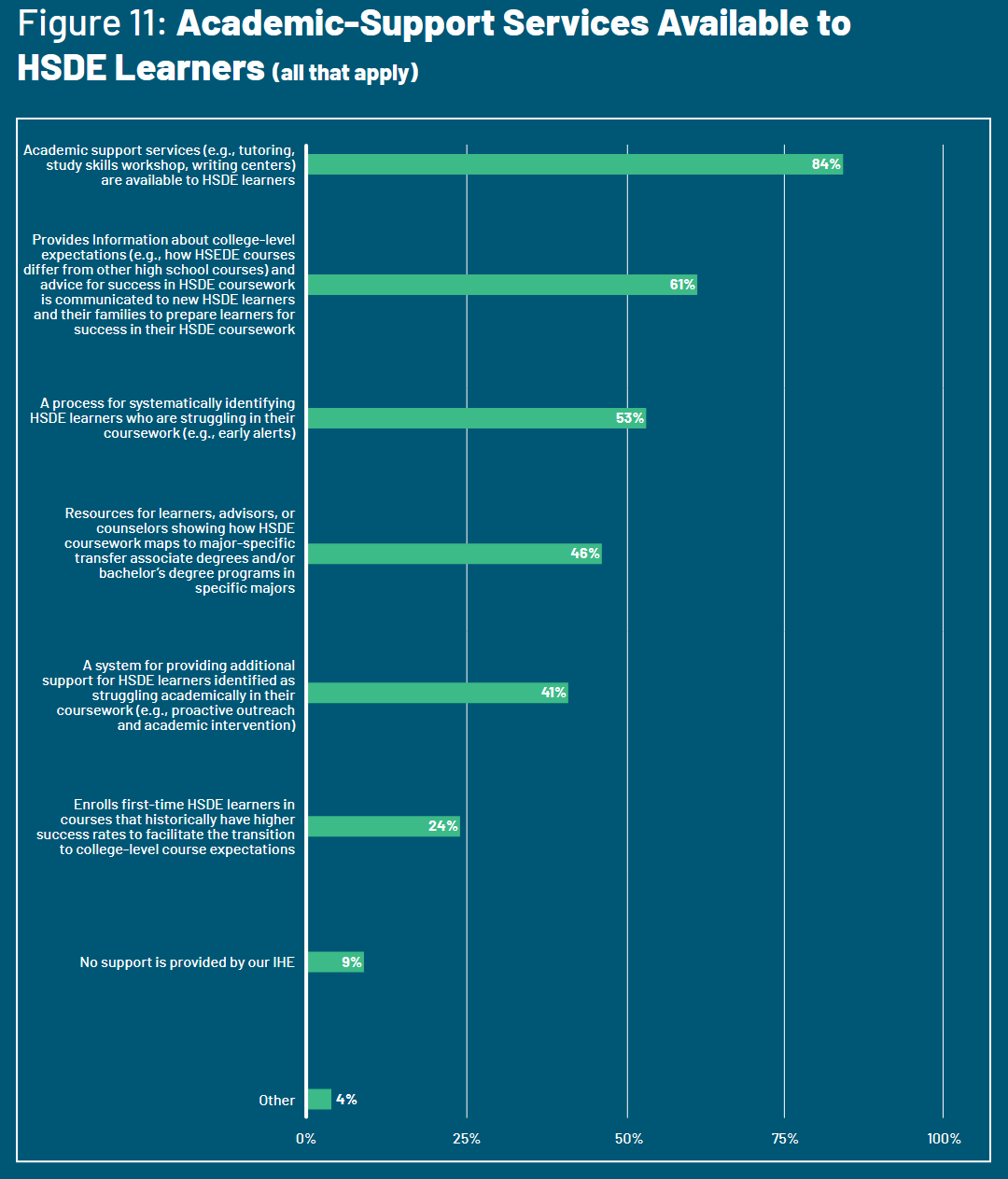

Of course, much depends on students’ performance and experience within HSDE. The report characterizes the supports provided to HSDE students as “robust.”

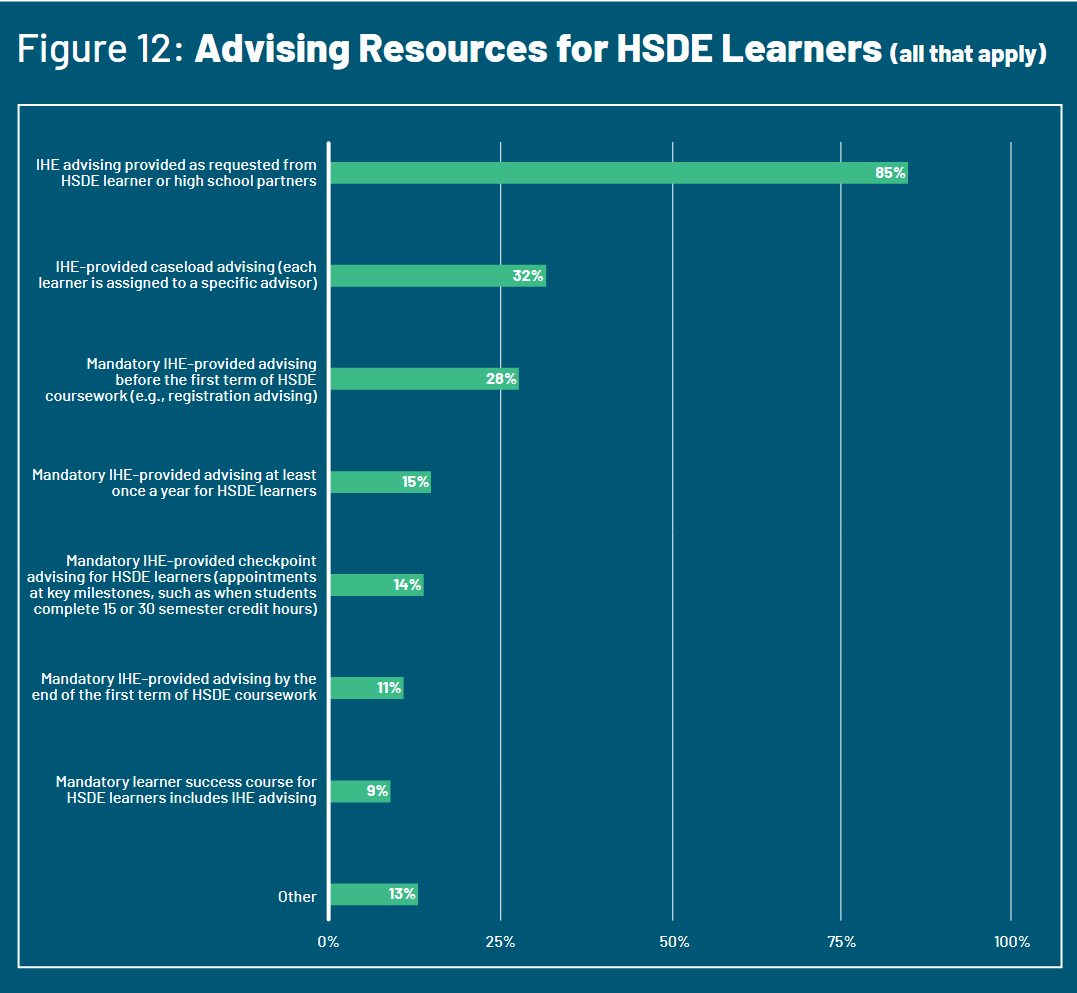

But, digging into the data, the robustness becomes less clear, especially when it comes to advising.

It’s encouraging that services such as tutoring and advising are available, but if they aren’t required or widely used, their impact may fall short of expectations. As the report notes, the differences between high school and college are substantial.

Culturally the roles and expectations of learners differ. High school learners are largely guided through their experience with structured schedules, frequent progress checks, mandated attendance, and support built into the fabric of the school day. [snip]

In contrast, college learners are expected to operate with a high degree of independence. They are presumed to manage their time , know how to find and seek help when needed, navigate new complex systems , procure their own learning materials and balance competing priorities

Given these differences, I worry that the supports offered to HSDE students, even when they exist, haven’t been redesigned for high school learners and their specific needs. This is especially concerning because HSDE is often students’ first exposure to higher education, a moment of particular vulnerability. I’m especially troubled by the lack of career guidance to help students choose courses aligned with their future plans. Taking a misaligned course can waste time and, worse, discourage students from college altogether.

The report notes that institutions with high HSDE re-enrollment and large HSDE populations tend to offer stronger wraparound support and decision guidance. But that’s a form of survivorship bias: these are places where students are already succeeding, and they’re typically larger institutions which are a minority among HSDE providers. According to the report’s own figures, 58% of institutions offering HSDE enroll fewer than 100 students.

At many of these smaller institutions, what Jenkins et al. call “random acts of dual enrollment” often emerge, individual course offerings not integrated into clear pathways, advising, or coherent program design. They define random acts of dual enrollment as.

The typical practice of high school students selecting coursework based on instructor availability instead of on how the course aligns with their education and career plans

I’d extend the concept to include HSDE approaches where supports aren’t redesigned for the students they serve and remain far from comprehensive. For example, the report doesn’t address services like library access and mental health support.

Dual enrollment has enormous potential to improve access and success in higher education, but it will only realize that potential if it’s delivered in ways that help students make the transition with strong, well-designed support.

It’s harder to get there from here

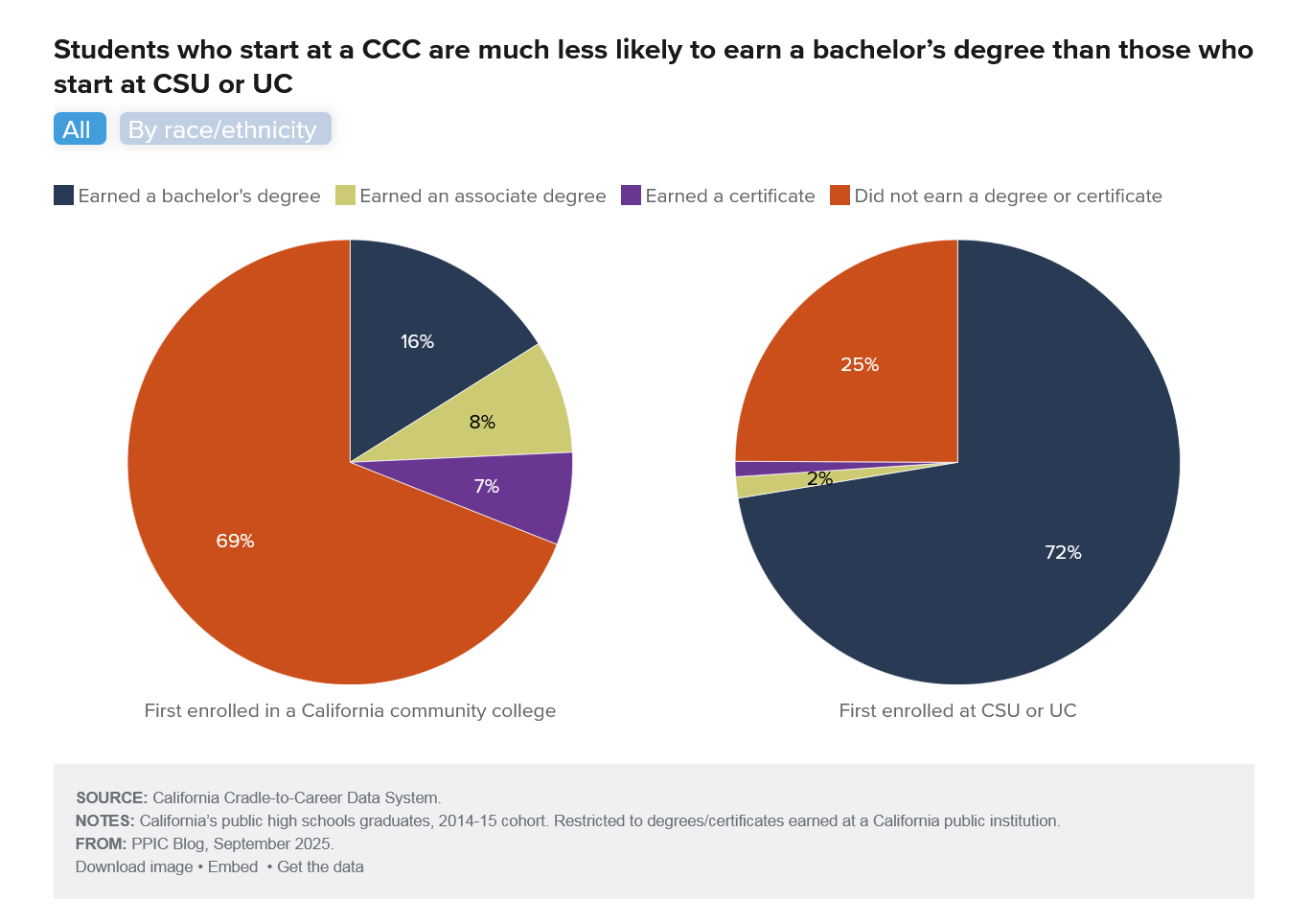

The Public Policy Institute of California offers a fascinating visualization comparing bachelor’s degree attainment rates for students who begin their higher education journey at community colleges with those who start at a California State University (CSU) or University of California (UC) campus.

We should be wary of drawing easy, and likely wrong, conclusions from these data. The students differ in important ways and often have different goals. But one major structural difference between students who start at a community college and those who start at a four year institution is that students who start at a community college and want a bachelor’s degree typically must transfer, whereas those who start at a CSU or UC generally do not. And the transfer system is still badly in need of repair.

Chilling effects

A new report from the British Academy (the U.K.’s national body for the humanities and social sciences) chronicles the impact of cuts to SHAPE programs—social sciences, humanities, and arts for people and the economy. (I’m not fond of the acronym; it sounds a bit like a spy agency.)

This is an important issue for two reasons.

First, program and discipline cuts are accelerating in several countries and will likely continue in the short to medium term. These decisions are neither easy nor uncontested; the more we understand their impact, the better prepared we’ll be to decide if, what, and how to cut.

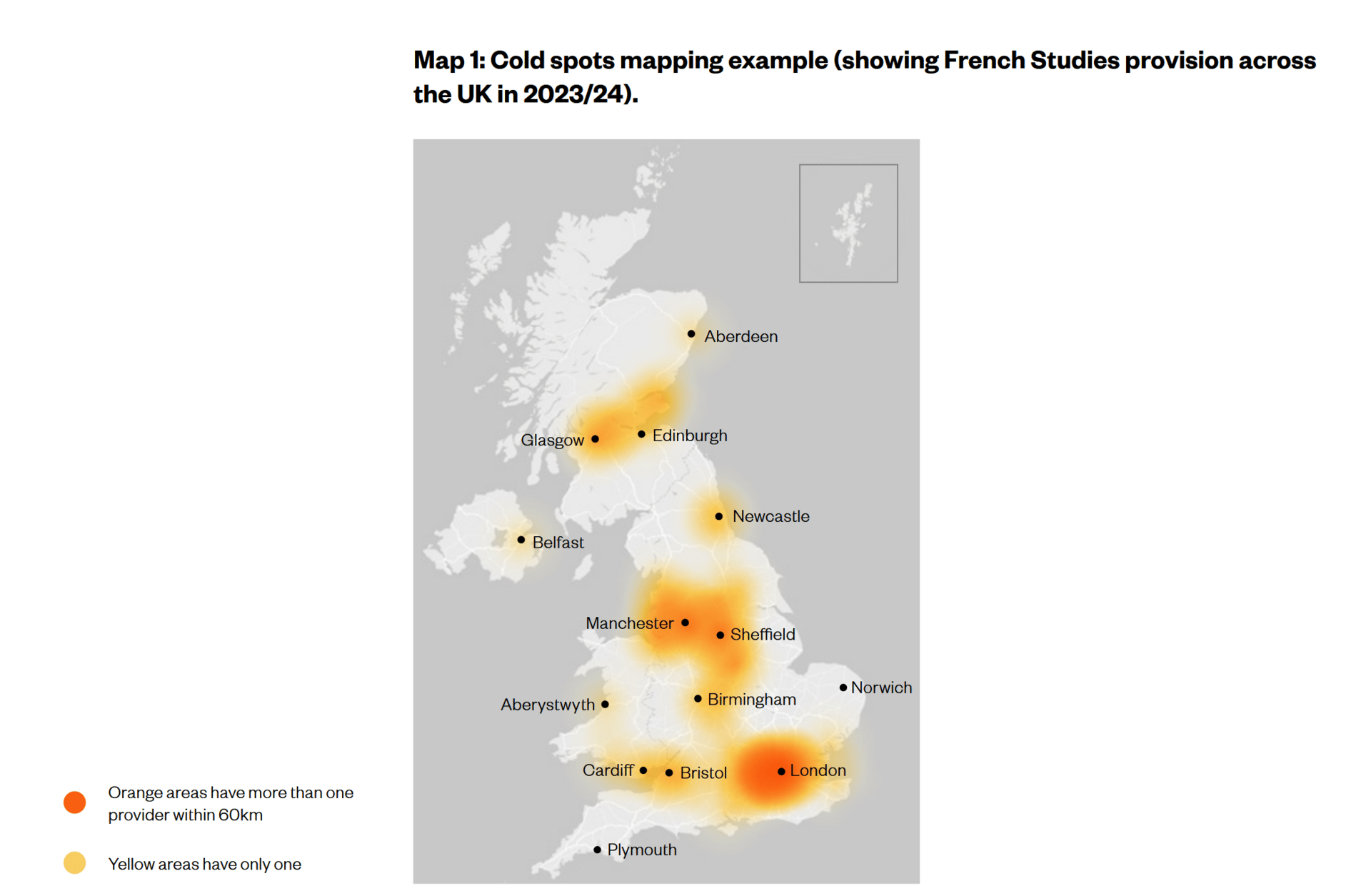

Second, the geography of higher-education access matters. Regulatory and fiscal pressures are reducing entire programs, especially in rural areas. As cuts continue, we need sharper tools for measuring local availability and its effects.

On both fronts, the British Academy report is useful. It notes that higher education is largely local: in the U.K., half of all students attend a university within 90 km of home, and a third within 30 km, patterns that are even more pronounced for disadvantaged students. When local options disappear, these students are hit hardest.

For SHAPE fields, nearby programs are increasingly scarce outside major urban centers, with the problem especially acute in modern foreign languages.

Programs in other disciplines, such as anthropology, are increasingly limited, and even fields like English and history are at risk.

However, the report is far less effective at proposing solutions. Its recommendations are thin, largely limited to monitoring the issue and encouraging more inter-institutional collaboration.

That’s weak sauce, and it may stem from the British Academy’s skepticism about the need for cuts in the first place; they state as much explicitly.

Decisions to cut courses [programs in American] are often a reaction to short-term projections of student demand, with quick fixes and coming at the cost of strategic vision and longer term viability.

I think they have a point, but denial is neither a strategy nor a tactic, and financial strain will win out every time. And it’s not as if you can’t make a case for SHAPE disciplines. Beyond their broader societal value, data consistently show that social science and humanities graduates often out-earn some technical fields over the longer term.

To me, this issue is a microcosm of higher education more broadly. Proponents of SHAPE need to do two things:

Take control of the narrative—be far more proactive and persistent in explaining and promoting the value of SHAPE and the skills these fields develop.

Do the hard yards to ensure SHAPE graduates have clear pathways into careers and strong support for the transition. It’s no longer acceptable to leave students to figure out how to translate their degrees into workplace skills on their own.

Rethinking the liberal arts

Interestingly, Brandeis University has just announced a plan redefining what a liberal arts education entails. That’s notable for two reasons: first, although Brandeis is a research university, it places a strong emphasis on the liberal arts and is moving earlier than many peers; second, it pairs that emphasis with an unusually strong STEM profile, making its approach especially instructive.

The new framework has four core components.

A redesigned core curriculum more suited to the demands of a global economy.

A new approach to career development, described in the following terms.

A second transcript that complements the traditional academic transcript to reflect skills and competencies obtained outside of the classroom.

A unified academic structure that fuses traditional liberal arts with professional education, for example combining a discipline with history with a more applied field such as business.

This is a fascinating development and will be an important process to watch. Tying the effort so explicitly to a product like Futurenav Compass carries some risk, especially since Brandeis will be among the first universities to adopt this tool and its approach to career planning.

Musical coda

Last night I saw the Wailin’ Jennys in concert for the first time since 2008, and it was an absolute treat. Enjoy.

The main On Student Success newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.