- On Student Success

- Posts

- This Week in Student Success

This Week in Student Success

Misunderstanding choice

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

Zora Neale Hurston once wrote.

There are years that ask questions and years that answer.

We are only a month in, but I am beginning to suspect that we are in an answering year: about what is important, where our values lie, and even about AI. I fear that I am not going to like all the answers, but even so, there is something to be said for clarity.

So what is new this week in student success?

What I read this week reinforced something I’ve been noticing for a while. We put enormous explanatory weight on the choices that students make: whether to go to university, what to major in, and which supports to use. But student success, and the choices themselves, are deeply shaped by the larger ecosystems in which those choices are embedded.

Student success is being judged more and more by outcomes. Yet those outcomes are shaped less by individual decisions and more by institutional systems that students often can’t access, don’t trust, or don’t benefit from equally.

It’s not the major, its the market

In explaining differential earnings by gender and race, we are accustomed to hearing explanations that attribute these gaps to choice of college major. Women and underrepresented minorities (URMs), we are often told, do not choose potentially high-paying majors, especially in STEM, and therefore tend to earn less than men and white students.

Some new research published by the NBER puts a serious dent in that argument. The researchers used administrative data from the state of Texas to track earnings over twenty years for graduates of Texas public schools working in STEM-related occupations. At some point, we do need to talk about the fact that so many of our insights come from research based on Texas data, and what that might mean. But that day is not today.

What they find is that if you look only at white or Asian graduates, major choice has some explanatory value. For everyone else, it has little. Within the same major, women and URMs are paid less, and this gap increases over time.

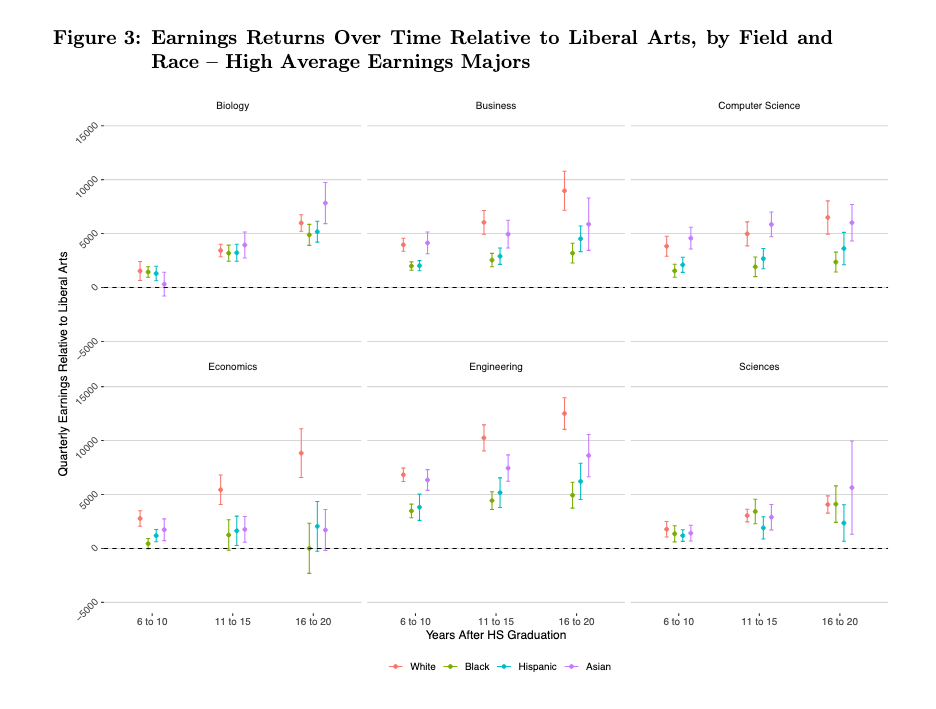

Focusing on STEM and higher earning fields (biology & health, business, computer

science, engineering, economics, science & math) in mid-career (16-20 years after high school), we estimate that women experience quarterly returns in each field relative to liberal arts that range from $1,101 to $4,564 below returns for men, equivalent to 8% to 34% of mean quarterly

earnings for women in our sample during this career stage. [snip]

Similarly, Black and Hispanic students experience far lower returns than White students in many high-earning fields. Relative to White students’ returns, Black students’ returns at mid- career in the fields listed above range from $39 higher to $8,826 lower than for White students (-0.3% to 70% of mean Black earnings). Hispanic students’ returns are between $2,879 and $6,788 lower than White students’ (21% to 49% of mean Hispanic earnings).

A similar pattern plays out in terms of race.

Similarly, Black and Hispanic students experience far lower returns than White students in many high-earning fields. Relative to White students’ returns, Black students’ returns at mid- career in the fields listed above range from $39 higher to $8,826 lower than for White students (-0.3% to 70% of mean Black earnings). Hispanic students’ returns are between $2,879 and $6,788 lower than White students’ (21% to 49% of mean Hispanic earnings).

What they do find is that occupational choices within specific majors explain some of the differences. Using complex methods, the authors show that much of the payoff from a major depends on which jobs graduates end up in, not on the major itself. Women and minority students are much more likely to end up in lower-paying occupations within the same field. When the authors simulate what earnings would look like if occupational sorting were equalized, most of the gaps disappear.

In other words, the problem is not mainly what students study. It is where they are able to go afterward, and who helps them get there.

This matters for how we think about “return on investment” in higher education.

If we are concerned about earnings, it is not sufficient simply to advise students to major in STEM and enter STEM fields. We also need to do a better job of helping students understand within-occupation choices and their implications.

We should also be skeptical of accountability data used to evaluate the ROI of degrees, such as that coming out of the recent OBBB in the US, that assumes similar payoffs for all students or relies on averages that obscure in-major differences in earnings. Failing to account for this risks penalizing institutions for labor-market dynamics they do not control.

Why students don’t use services

If outcomes depend on what happens after graduation, they also depend on whether students can navigate support while they are still enrolled. A while back, I wrote about a Tyton Partners report that seemed to point to a fairly straightforward problem: a mismatch between the kinds of support institutions provide and the kinds of support students say they want. The implicit story was that students weren’t using services because they didn’t know about them, couldn’t access them easily, or didn’t see how they were relevant.

A more recent report from Tyton Partners complicates that story.

Its updated visualizations again show large gaps between institutional availability, student awareness, and actual use of support services. On the surface, this looks like a familiar problem: institutions build services, advertise them imperfectly, and students fail to take advantage of them.

But when you look more closely at why students say they don’t use available supports, a different pattern emerges.

The top three reasons students give have nothing to do with logistics. They are:

“I want to do things on my own.”

“Support is not for students like me.”

“I doubt it will be helpful.”

Taken together, these point to something much deeper than a communication problem. They suggest a lack of trust in the support itself.

In other words, this is not primarily a visibility problem. It is a legitimacy problem. Support that lacks legitimacy becomes invisible, no matter how visible it is.

Many students do not experience institutional support as something designed for people like them, in situations like theirs, and at moments when they actually need it. Instead, support is often perceived as remedial, stigmatizing, bureaucratic, or disconnected from real academic and personal challenges. For some students, using support feels like admitting failure. For others, it feels like entering a system that does not understand them.

This helps explain why awareness alone does not translate into use.

In many ways, this mirrors a familiar challenge in faculty development. Institutions regularly offer training in areas such as online course design, assessment, or inclusive teaching. Faculty are aware that these programs exist, and many agree they are important. Yet participation remains uneven. Highly skilled professionals often resist guidance that feels generic, misaligned with their context, or disconnected from their day-to-day work.

With students, the dynamic is similar—but the stakes are higher. Institutions are working with learners who may be unfamiliar with how universities operate, uncertain about their own standing, and sensitive to signals about belonging and competence. When support systems fail to account for this, they quietly lose credibility.

Some barriers are still practical. Long wait times, limited hours, lack of walk-in availability, and inflexible modalities continue to matter, and there is little excuse for allowing these problems to persist.

But the larger challenge is cultural and relational.

If students do not believe support will help them, will respect them, or will understand their circumstances, they will not use it, no matter how well funded or widely advertised it is. Addressing that gap requires more than better marketing. It requires rethinking how support is designed, delivered, and embedded in students’ everyday academic lives.

It also suggests a need for much more qualitative research into how students actually experience institutional support, and how those experiences shape trust over time. Until institutions understand that, they will continue to invest in services that exist on paper but fail to function in practice.

A sad horse for an answering year

This odd story captures something about how many people in higher education seem to be feeling right now. A factory in China accidentally stitched a scowl onto the face of a stuffed horse -it is the Chinese Year of the Horse—turning it into an unintended bestseller.

In the Year of The Horse at least some aren’t liking the answers so far.

Moving on up

Student social mobility, that is, the ease with which students can achieve high levels of income, is a critical aspect of student success. A new report from the Sutton Trust provides some fascinating insights into this issue across multiple countries.

The report examines the relationship between higher education and social mobility, defining mobility as reaching the top 20 percent of the national earnings distribution. It is important to note, however, that this definition focuses on reaching the top quintile without referencing where students might have started.

The authors find that mobility varies enormously across countries, but that it is deeply shaped by whether students’ parents have a degree themselves.

In every country, individuals with graduate parents are more likely to reach

the top of the earnings distribution. In the UK, about one in three adults

with graduate parents are in the top quintile, compared with one in five of

those from non-graduate families.

[snip]

Overall, this headline comparison highlights the persistence of inequality

of opportunity: family background remains a strong predictor of outcomes

If parental education shapes access to high-paying occupations, then advice focused on choice of major or institution misses the point. This is an angle that is implied but not fully explored in the otherwise excellent work of scholars such as Raj Chetty.

If it works, why aren’t you using it?

A report from RNL (now part of Encoura) left me puzzled for two different reasons.

On the one hand, the data suggest that institutions are making very limited use of AI-driven tools for student success. On the other, the report describes extraordinarily high effectiveness among the small number of institutions that say they are using them.

Despite high effectiveness ratings, actual AI implementation remains surprisingly low across all institution types.

Those two findings do not sit comfortably together.

According to the report, only small fractions of institutions say they are using AI in areas such as early alert systems, academic advising, or proactive outreach. For example, just 6 percent of four-year private institutions, 11 percent of four-year publics, and 3 percent of two-year institutions report using AI in early alert communications.

These usage rates are lower than I would have anticipated.

One possibility is that they understate reality. Many early alert systems and CRM platforms now embed some form of machine learning or automated pattern detection. It is plausible that some respondents are using AI-enabled tools without labeling them as such.

But even if that explains part of the gap, it cannot explain all of it. The overall picture still points to very limited and uneven adoption.

The second puzzle is the report’s claim that early alert systems using AI are 100 percent effective.

At best, this reflects the limitations of self-reported survey data. At worst, it reflects wishful thinking.

Over the past decade, I have repeatedly asked institutional leaders whether early alert systems have clearly and consistently improved student outcomes at their institutions. In all that time, I have received only one unequivocal yes. More often, the answer is some version of “it helps in certain cases” or “it works when everything else is in place.”

That experience makes a universal effectiveness rating deeply implausible.

What the RNL data likely captures is not objective impact, but perceived usefulness among a small, self-selected group of early adopters. Institutions that invest heavily in these tools, integrate them into workflows, and assign staff to act on the data are more likely to view them positively. Institutions that struggle to operationalize them either do not adopt them at all or abandon them quietly.

Seen this way, the real story in this report is not about AI’s technical potential. It is, once again, about institutional capacity.

AI tools for student success do not work in isolation. They require clean data, integrated systems, clear governance, trained staff, aligned incentives, and sustained attention. Without those conditions, they generate dashboards rather than decisions, and alerts rather than action.

This helps explain the paradox of low adoption and high reported effectiveness. Where institutions have built the surrounding infrastructure, AI can amplify human work and improve targeting. Where they have not, it adds another layer of complexity to already strained systems.

It is the student success Groundhog moment: new tools, new reports, new dashboards, same structural constraints. Across earnings, support, mobility, and AI, the same ecosystem problem keeps resurfacing. This is not primarily a technology problem. It is an organizational and systemic one.

I suspect this will not be limited to Groundhog Day, and that we will keep returning to it in this year of answers.

Musical coda

I came across this, oddly enough, through a recommendation from Adam Savage, and I’ve been enjoying it. Bowie is a tough artist to cover, and “Life on Mars” is an especially difficult song.

On Student Success is free, and you are welcome to share it (with attribution).

Last week, I asked you not to forward it, in order to preserve the illusion of a small, slightly secret society of people who enjoy thinking too much about higher education.

This week, I am reluctantly conceding that some of your friends probably belong in that society too.

Thanks for being a subscriber.