- On Student Success

- Posts

- This Week in Student Success

This Week in Student Success

Data, doubts, and the danger of easy fixes

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

It’s almost here! The event I’ve been looking forward to for months: the Women’s Cricket World Cup begins on Tuesday. The real challenge will be figuring out how to fit in everything I need to do around all those matches.

But, what happened this week in student success?

The least effective student supports are the ones you don’t use

In the spirit of eating one’s vegetables first, I’m starting with one of the pieces of news this week that frustrated me most (admittedly that’s a very large category).

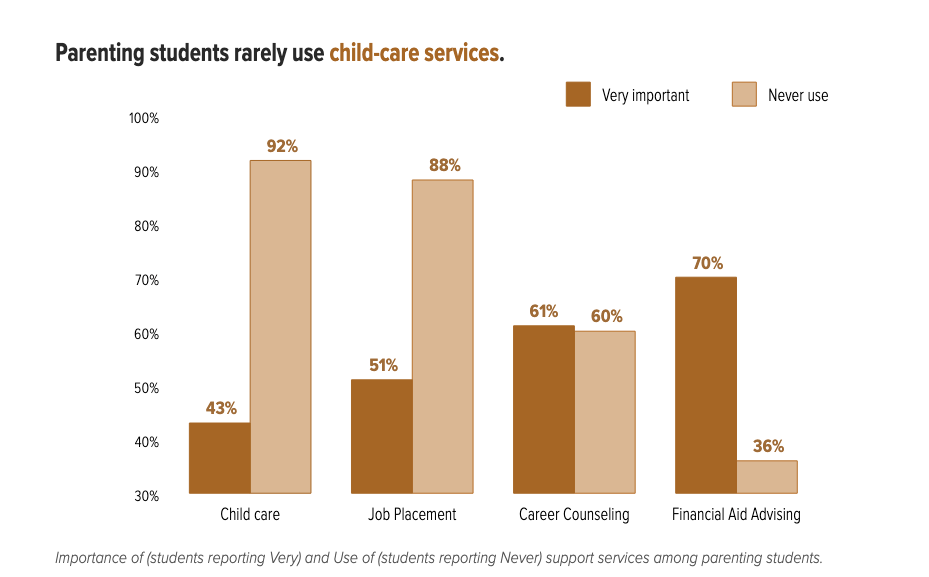

The Community College Survey of Student Engagement (CCSSE) report on student parents confirms much of what we’d expect: they need greater flexibility, and most are women. But the survey’s findings on under-utilized student supports are maddening. It’s almost as if the services student parents need most are the ones they use least.

While we sometimes over-ascribe rationality to people’s actions, this data again highlights a serious problem in how, and where, student supports are provided. I really do need to get on to the second part of my post about the design of student supports.

Undergraduates down under

Australia’s QILT has released the national report from the 2024 Student Experience Survey, billed as the most comprehensive snapshot of student experience in the sector.

the only comprehensive survey of current higher education students in Australia. It focuses on aspects of the student experience that are measurable, linked with learning and development outcomes,

The survey examines the student experience across six areas:

Skills Development

Peer Engagement

Teaching Quality and Engagement

Student Support and Services

Learning Resources

Overall Educational Experience

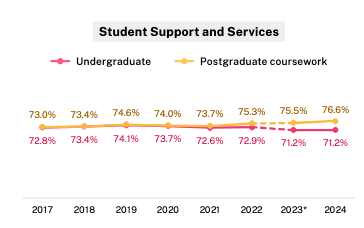

There’s a lot of valuable data in the survey, but one finding jumped out at me: signs of an emerging problem with undergraduate student support. This measure captures “the helpfulness of various supports and services provided by institutions, including administrative, career development, health, and financial services,” in other words, the typical student-success infrastructure. The trend line isn’t good. Undergraduate support ratings are diverging from postgraduate ratings and are now lower than at any point since 2017.

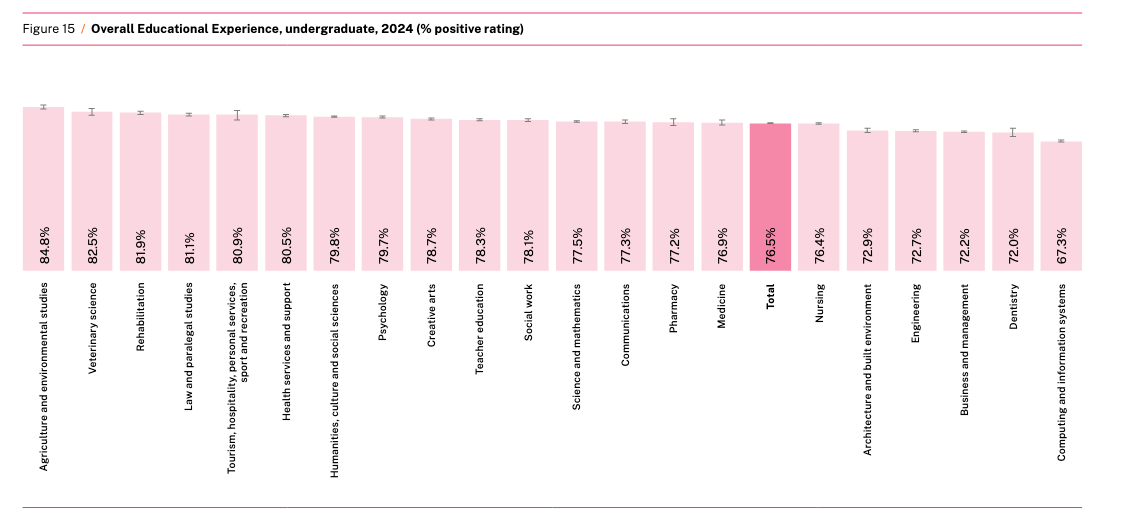

In contrast, undergraduates and postgraduates were remarkably similar in their ratings of Overall Educational Experience—76.7% positive for postgrads and 76.5% for undergrads.

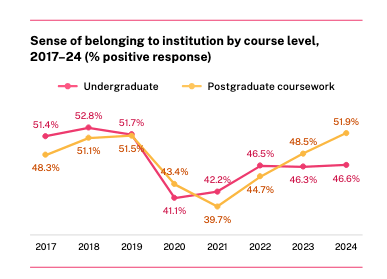

But even more concerning than undergraduates’ declining satisfaction with support services is their low sense of belonging. QILT defines this as.

feelings of connectedness, inclusion, and acceptance, [which] is crucial for academic achievement, personal wellbeing, student satisfaction, and retention. These ratings dropped markedly in 2020 due to the pandemic.

Also—what the heck is going on with computer science? Sure, someone has to be at the bottom of the pack on experience, and if this were a prediction quiz I probably would’ve guessed CS (do I win anything?). But the gap between CS and, say, veterinary science—no walk in the park and often pretty grim—is striking.

The other, more important, meta

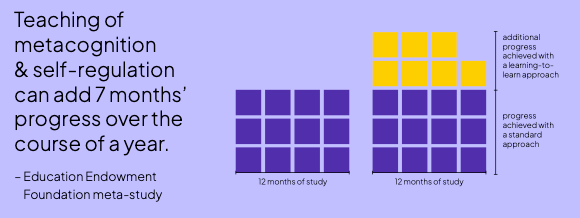

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about some of the discourse around skills in higher education. I expressed concern that much of the conversation about student success doesn’t pay enough attention to skills, and argued that we need to place greater emphasis on “learning to learn.”

You can hardly open a newsletter or an article in the higher education trade press without stumbling across yet another list of the “top ten durable skills” graduates supposedly need to succeed in the workplace. And, almost invariably, the underlying message is that most graduates don’t have them.

[snip]

But even with their length, what most of these lists seem to leave out is the ability to learn how to learn.

Pearson has a new report on the difficulties many people face when making career transitions—and the economic losses that result. The transitions in view include moving from college or university to the workplace, shifting from one job to another, and reskilling or upskilling.

What fascinated me, though, was a small sidebar on the importance of learning to learn.

a meta-study of 246 studies by the Education Endowment Foundation found that metacognition and self-regulation approaches to teaching (essentially, helping pupils to think about their own learning more explicitly, through specific strategies for planning, monitoring, and evaluating their learning) rank as having the most effective impact on student outcomes and can add seven entire months of progress over the course of a year. That’s a powerful multiplier effect.

Even though the Education Endowment Foundation has such a bland, bureaucratic-sounding name—it almost makes it sound like part of a national intelligence agency, this study is one I should definitely read.

Miracle cure

A couple of years ago, I was giving a talk on student success at a mid-sized regional institution in the South. As I was waiting to begin, a senior administrator told me I was too late, they’d recently made big gains in student success. Before we even got to the metrics, I asked how they’d done it. He said they’d raised admissions standards and were admitting fewer Pell-eligible (i.e., low-SES), first-generation, and similar students.

Which gets to a sad but unavoidable truth about student success: it’s possible to game the numbers, and it happens far more often than we’d like.

That’s why a post this morning from Freddie deBoer on the absence of “miracles” in education caught my eye. It’s about K–12, but the lessons apply to higher ed as well.

In it, deBoer examines a newsletter celebrating dramatically improved test scores in Mississippi, the so-called “Mississippi Miracle.”

And I usually disagree with him about just about everything. Kelsey Piper has an exceptionally credulous piece about the supposed “Mississippi miracle,” which is the claim that Mississippi public schools have seen a sudden and dramatic increase in their quantitative educational metrics through the application of a little want to, a little know-how, and an extra dash of love. Supposedly, in defiance of a hundred years of experience in large-scale education policy in the developed world, some pedagogical tweaks have enabled educators in Mississippi [snip] to ignore the conditions that have caused these interventions to fail again and again and again.

Freddy isn’t buying it. He argues that what some see as a “miracle” is more likely just good old-fashioned number-fudging, something he’s seen time and again in K–12 over the years.

Unfortunately [snip] none of this optimism ever lasts. The odds are very, very strong that eventually it’ll turn out that students in Mississippi and other “miraculous” systems are being improperly offloaded from the books or out of the system altogether and this will prove to be the source of this supposed turnaround. That’s how educational miracles are manufactured: through artificially creating selection bias, which is the most powerful force in education. After all, there’s something very conspicuous in its absence in Piper’s piece: the so-called “Texas miracle,” a very, very similar scenario that played out some quarter-century before anyone was talking about a Mississippi miracle. The story was genuinely almost identical: George W. Bush won the governorship in Texas, made some “common sense” curricular changes, and began to demand ACCOUNTABILITY from public teachers and schools… and suddenly, a miracle happened. The schools got better! The test scores proved it!

Because it turns out that what happened in Texas was not that students were being supported and coached into succeeding. The ones who weren’t succeeding just weren’t being counted.

Later investigations revealed exactly what we should always expect to find in the face of supposed education miracles: the manufacture of selection bias through widespread underreporting of dropouts, “disappeared” struggling students, and data manipulation. Students who had dropped out were given phony classifications such as having transferred or moved into GED programs, meaning that negative dropout metrics weren’t reported; Sharpstown High School in Houston reported a 0% dropout rate in 2001-2002, even though hundreds of students left the school. Abuse of special education exemptions for testing/accountability was rampant, with the number of students in some districts doubling between 1994 and 1998. Meanwhile the state’s standardized tests were being consistently misinterpreted (in one direction, up) thanks to a complete failure to account for measurement error. The “miracle” collapsed when all of this skullduggery was revealed. Texas’s real outcomes were exposed as unremarkable, once the missing data was analyzed, and other state efforts to replicate the supposed miracle failed entirely.

I can only aspire to the level of snark Freddy brings to this post, and while I usually disagree with him about almost everything, this is an important issue, covered well. It is also an issue that gets far too little attention in higher-ed student success discussions. The methods differ from K–12, though. More often, I see the “number-jiggling” happen in a few ways:

Announce, don’t account. Launch student success initiatives with great fanfare, then never report results. I know more than a few higher-ed CIOs who’ve built careers this way—announce, move on to the next job or the next initiative.

Adjust the inputs. As the knee bone is connected to the thigh bone, student success metrics are connected to admissions. Make your institution far more selective and, unsurprisingly, you’ll face fewer student success challenges. You’ll also likely do a worse job on access.

Focus on a sliver. This is my core concern with programs like CUNY ASAP. They’re terrific for the relatively small number of students who get in, but outcomes for those left out don’t improve, and the scalability of the model is very difficult if not impossible.

Musical coda

An instrumental Life on Mars, on what seems to be Mars

The1 On Student Success newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.

1