- On Student Success

- Posts

- This Week In Student Success

This Week In Student Success

Thank you for the feedback

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

This week in Morgan success I managed not to eat any Halloween candy purchased for the “trick or treaters.”

But what happened in student success?

The fellowship of the hype

It seems like everyone is talking about the Wall Street Journal piece on the Palantir Fellowship, where the company offers 22 high school graduates the chance to skip college and work at the analytics firm for a year, with the possibility of a permanent job.

The idea isn’t new, nor is the notion of delaying college (I’m old enough to remember when we just called it a “gap year”). Palantir was co-founded by Peter Thiel, a fact curiously absent from the article. Thiel, of course, also created the Thiel Fellowship, which gives students who forgo college $200,000 over two years to “build new things instead of sitting in a classroom.” The program typically supports 20–30 fellows annually, and many alumni have gone on to found successful companies, Dylan Field, co-founder of Figma, among them.

Palantir’s program appears to be an adaptation of the Thiel model.

I have several major problems with the concept, and especially with the WSJ’s coverage of these fellowships.

First, this is not education or workforce policy. Most recipients of Thiel Fellowships, or Palantir’s, are likely highly intelligent, driven individuals who would have succeeded anyway. For example, recent Thiel Fellow Brendan Foody, founder of Mercor, is described in a profile thus.

Foody and Co. grew up around tech. All three are the children of software engineers. Foody’s mom worked for Meta’s real estate team and his dad founded a graphics interface company in the 90s before turning to startup advising. One of his first ventures, as a high schooler at age 16, was a company to get his friends promotions on Amazon Web Services, the ecommerce giant’s cloud platform, charging them $500 each.

Needless to say, most students don’t arrive at college with that kind of background or experience. For the vast majority, jumping straight into the workforce after high school isn’t a viable path to a professional or white-collar job.

Second, unlike Palantir, most workplaces aren’t committed to providing on-the-job training or sustained professional development. Employer spending on training has declined in the US, and in the UK it has dropped by nearly 20% over the past decade. Students who forgo post-secondary education risk landing in dead-end roles, unless they make a significant personal investment of time and money to build their skills.

Third, although Palantir representatives are openly dismissive of higher education, questioning its meritocracy, excellence, necessity and format, the fellowship includes what looks suspiciously like a higher-ed–style seminar series, taught at least in part by people affiliated with mainstream universities.

The fellowship kicked off with a four-week seminar with more than two dozen speakers. Each week had a theme: the foundations of the West, U.S. history and its unique culture, movements within America, and case studies of leaders including Abraham Lincoln and Winston Churchill.

How this differs from what happens in higher education, and why this version of “sitting in a classroom” is acceptable while the versions at places as different as Reed College and New College are not, goes unexplained (although I think the word I am looking for here is hypocrisy). It’s also unclear why what Palantir Fellows do counts as “building things,” while the work happening in classrooms and labs across the country, or in co-ops like at at Northeastern and the University of Waterloo, supposedly does not. In fact, the only concrete activity described in the article is “taking notes,” which sounds less like building and more like administrative support.

Fourth, it’s a stretch to call this a fellowship or to cast it as a true alternative to college. The program lasts four months, essentially a single semester, and seems to function more like part of a gap year.

Finally, despite the WSJ’s framing (and perhaps Palantir’s), this kind of program is a tiny blip, not a dismantling of higher education. Roughly 3.9 million students graduated from U.S. high schools this year; Palantir awarded 22 fellowships. Even adding the Thiel Fellows, the scale remains minuscule. For reference, just over 100 Rhodes Scholarships are awarded annually. The article reads like the endless New York Times focus on the Ivies, as if they represent the entirety of higher education, only more so.

Despite these flaws, articles like this still do real damage to public understanding. Higher education needs to make a stronger, clearer case for why it remains a worthwhile and essential sector of society.

The produce section of skills

I recently wrote about durable skills, and we’re hearing more and more about them. What we hear far less about are perishable skills; those that require frequent updating because they’re tied to specific technologies, governed by fast-changing regulations, or prone to decay without regular practice. It’s an important concept, and one we should discuss more often.

Mixing feedback, carefully

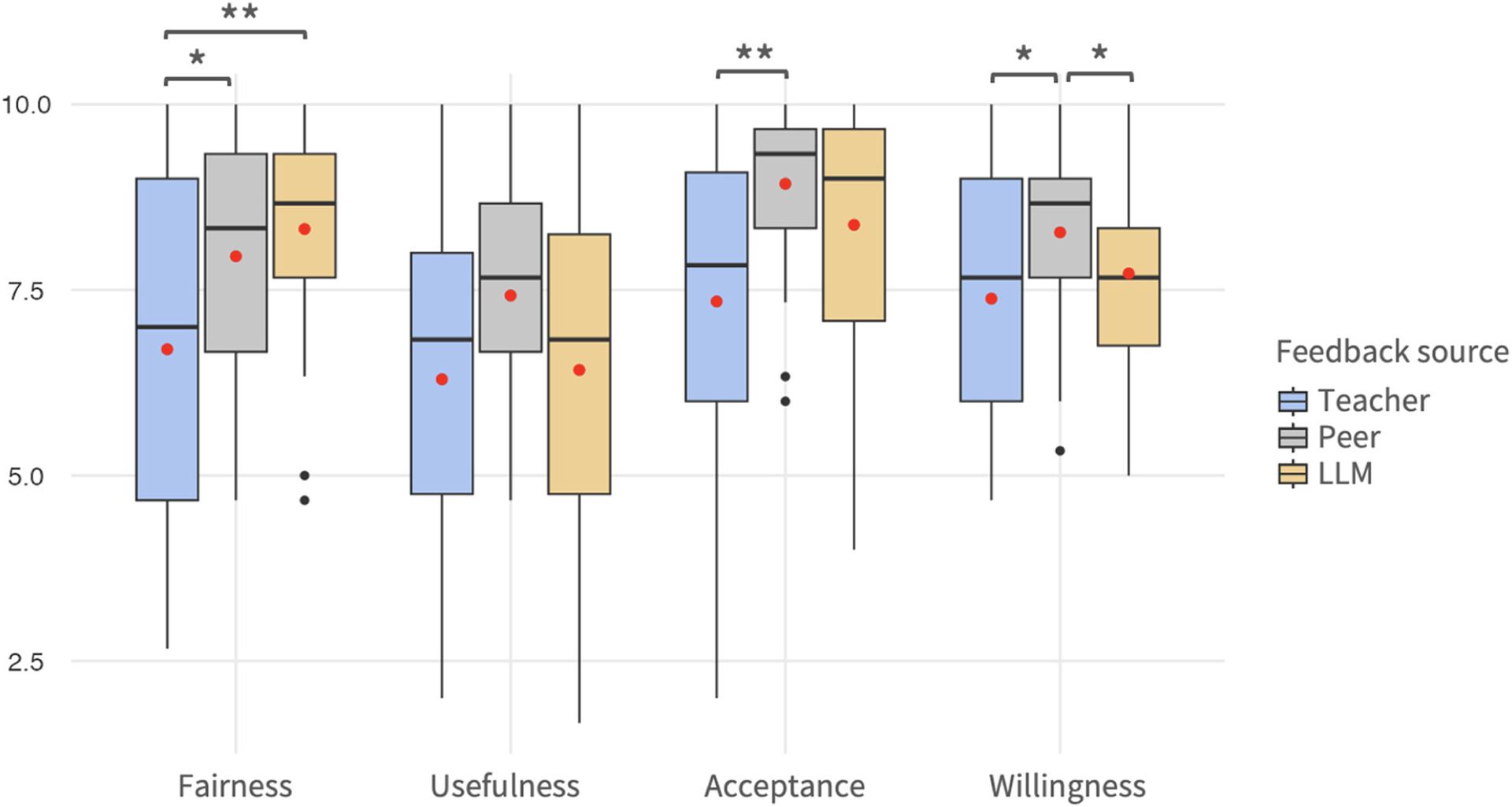

A new study on student perceptions of feedback offers limited but intriguing insights about how the source of feedback matters. The research is small and has several limitations, but it carries important implications for the essential work of giving feedback, especially when AI systems are in the mix.

Using a randomized field experiment, Joshua Weidlich, Flurin Gotsch, Kai Schudel, Claudia Marusic-Würscher, Jennifer Mazzarella, Hannah Bolten, Dario Bütler, Simon Luger, Bettina Wohlfender, and Katharina Maag Merki compared student reactions to feedback from instructors, AI, and peers. About 90 students in a single course were organized into discussion sections, and students received blinded feedback so they wouldn’t know the source.

That is, the feedback did not indicate the source of the feedback and thus students were unaware of the feedback source––although, of course, students were informed that they would be receiving feedback from one of the three sources [snip]. Blinding ensures that any observed feedback effects were attributable solely to the feedback's content rather than its perceived origin and potential student biases or preconceptions.

The authors examined students’ perceptions of feedback in terms of fairness, usefulness, acceptance, and their willingness to revise their work based on it. Students rated peer and AI feedback as fairer and more acceptable than teacher feedback, likely due to its tone and perceived non-judgmental style

The authors also examined how feedback affected objective outcomes. They looked at content quality, scientific argumentation, and the formal quality of students’ work (i.e., following directions and formatting). All feedback types led to improvements, but instructor feedback produced the strongest gains in scientific argumentation, while peer feedback yielded the biggest improvements in formal quality.

Finally, they tested whether feedback literacy and motivation moderated these effects. Using a short external instrument, they found that students with higher feedback literacy viewed instructor feedback as fairer, and improved more after receiving it. Students with higher intrinsic motivation were more likely to accept and act on feedback, especially AI-generated feedback.

Implications

The authors conclude that carefully combining different types of feedback, while strengthening students’ feedback literacy and intrinsic motivation, is likely to have the greatest impact on both achievement and satisfaction. However, the goal isn’t simply to mix feedback sources randomly, but to align each type of feedback with specific learning needs: teacher input for higher-order reasoning and complex argumentation, and peer or AI feedback for more routine work.

Taken together, our findings suggest that carefully combining feedback sources while also laying the groundwork for feedback uptake by supporting students’ feedback literacy and intrinsic motivation could be particularly powerful to foster a constructive feedback culture in the classroom. Instead of relying on LLMs as stand-alone solutions, educational designs could combine immediate AI feedback with structured opportunities for reflection, peer discussion, and teacher follow-up to promote deeper engagement and critical evaluation of feedback. [snip] Rather than suggesting a general “mix of sources,” our findings indicate that teacher input is best reserved for cognitively demanding, higher-order aspects, while peer and LLM feedback can effectively support more routine or formal dimensions of writing. Combining these sources therefore entails a division of labor aligned to their comparative strengths

They also recommend leaning in to feedback literacy and working to foster it in students.

This confirms arguments [snip] that feedback literacy should be treated as an essential learning outcome in its own right. Importantly, building feedback literacy is not a passive process but requires structured interventions, such as explicit instruction on how to interpret and apply feedback, guided peer review activities, or reflective exercises that prompt students to evaluate and plan based on received feedback. Embedding these activities across the curriculum—rather than treating feedback as a one-off event—could help cultivate a more feedback-savvy student body capable of benefiting from a broader array of feedback sources, including AI systems whose pedagogical quality may vary.

Similarly, they recommend institutions act to build motivation within their students, particularly if AI-based systems are going to be used.

Therefore, efforts to foster intrinsic motivation—through autonomy-supportive teaching, emphasizing relevance and personal meaning in assignments, and giving students agency in their learning pathways—may be necessary complements to the implementation of AI-enhanced feedback systems.

Hah!

One of the limitations of the above study is that it is a randomized control trial (or a version of one). Some of you know how I feel about those. And in honor of Halloween.

Musical coda

Dave Ball from Soft Cell died just over a week ago. In his honor, Tainted Love, in the extended version, which is the only way to listen to it.

The main On Student Success newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.