- On Student Success

- Posts

- This Week in Student Success

This Week in Student Success

Nontraditional

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up for the On Student Success newsletter and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week.

What is new in student success this week?

Before we start, a reminder from the corgi world: it’s not always the most obvious types who succeed, nor those who are quickest out of the gate.

But, more seriously, many of this week’s stories point to the same uncomfortable truth: student success is increasingly shaped by institutional design choices that sit outside the classroom, and often outside the metrics we rely on to judge success at all.

Dual enrollment as upstream student success

In a recent newsletter, I wrote about an AACRAO report that criticized the way dual enrollment is often approached at U.S. colleges and universities. Dual enrollment (DE), the practice of allowing high school students to enroll in credit-bearing college courses, is becoming an increasingly important part of overall enrollment, and of community college enrollment in particular. Today, DE accounts for roughly 12% of all undergraduate enrollments and a striking 21% of community college enrollments.

But much of this growth has been unplanned. The AACRAO report describes how, too often, DE ends up as a series of “random acts of dual enrollment.” Programs are frequently disconnected from clear pathways into postsecondary education or from meaningful career outcomes for students.

There is also a clear equity dimension to this ad hoc approach. The students most likely to participate in DE are often those who were already planning to attend college. As a result, DE can unintentionally reinforce existing inequalities rather than mitigate them.

Against this backdrop, the Community College Research Center (CCRC) has issued a new report calling for a fundamentally different approach, what it explicitly describes as a new business model for dual enrollment. CCRC argues that the current laissez-faire model will not deliver on its attainment and equity promises unless colleges rethink how DE is structured, resourced, and supported.

CCRC’s proposed alternative is what they call Dual Enrollment Equity Pathways (DEEP). The DEEP model involves higher upfront investment paired with intentional advising, pathway alignment, faculty oversight, and close partnerships with K–12 systems. The goal is not simply to expand access to DE, but to reach students who might not otherwise see themselves as college-bound, and to ensure that early exposure to college coursework translates into later postsecondary success and meaningful career outcomes.

CCRC identifies a set of core components that go well beyond what most community colleges currently provide to DE students. These include:

Targeted outreach by colleges to promote dual enrollment opportunities, with a specific focus on underserved communities.

Intentional alignment of dual enrollment coursework with bachelor’s degree pathways, career-technical associate degrees, and apprenticeship programs in high-opportunity fields.

Advising and student support provided by the college to help students explore program options, choose program-relevant coursework, and develop personalized postsecondary plans.

High-quality instruction, paired with intrusive and proactive academic supports to ensure students succeed in their dual enrollment courses.

Close, ongoing partnerships with K–12 schools and districts to support program planning, day-to-day operations, and problem-solving.

These kinds of interventions would no doubt have a meaningful impact on student success, but they represent a significant lift, especially for community colleges, which are already stretched thin.

Part of my hesitation with the report stems from its loose use of the phrase “business model.” At its core, the argument is that upfront investment in dual enrollment will pay off later through increased enrollment and improved student success.

The report treats dual enrollment as a long-term enrollment investment, but without a clearly articulated theory, or evidence, showing how today’s costs reliably translate into future completions. In doing so, it frames dual enrollment primarily as a problem of resource allocation and long-term sustainability. While the case for upfront investment is persuasive, the report stops short of demonstrating a clear return on that investment. For now, the payoff is assumed rather than empirically established.

That said, I am drawn to the report’s implicit framing of dual enrollment as an upstream investment in student success. The challenge for higher education is that the scope of student success continues to expand. Institutions are increasingly being asked to think about student success not only during students’ time in college, but also before they arrive and after they leave.

Bureaucracy eats policy for breakfast every time

If dual enrollment shows how student success is increasingly shaped before students ever arrive on campus, administrative holds illustrate how easily it can be derailed once they try to return.

A new Ithaka S+R report usefully illustrates a problem that often gets lost in policy discussions about re-enrollment: even when federal rules change and states invest in initiatives to bring students back, institutional workflows can still quietly block progress. Administrative holds, often the result of routine bureaucratic processes rather than intentional policy, remain a significant barrier to re-enrollment, largely because of breakdowns in communication and unclear ownership.

Ithaka examined more than twenty institutions in New Jersey, drawing on interviews, a survey, and institutional data. The context matters. Since July 1, 2024, higher education institutions have been sharply limited in their ability to impose transcript holds that prevent students from transferring credits or accessing employment opportunities. On paper, this represents a meaningful policy shift. In practice, however, administrative holds tied to unpaid balances and other issues continue to affect students, in part because once a hold is placed, it can be surprisingly difficult to determine who put it there, or how to remove it.

As the report notes.

Once they have been placed on a student’s account, ownership of holds can be unclear and difficult to ascertain. One interviewee shared, “Sometimes it’s the human error of who is managing it, not knowing who is requesting the list, who is advising the list, who is removing the holds.” For example, different departments may have the ability to add or remove holds, but not everyone within a department can do so, making it challenging to clearly and quickly identify the right person to remove a hold from a student’s account. Technology challenges and coding errors may also contribute to confusion, as they can make the purpose and resolution process unclear.” The result, as Ithaka succinctly puts it elsewhere in the report, is that holds can “create a labyrinth for students to navigate once a hold is placed on their account.

Some institutions are responding constructively, improving communication with students through multiple channels when registration is blocked, and strengthening coordination across offices through one-stop or centralized service models. Those efforts are encouraging. But the broader takeaway is harder to ignore: the fact that bureaucratic snafus and internal communication failures can prevent students from re-enrolling—either at their original institution or a new one — is unconscionable. If institutions are serious about re-engaging students with some college and no degree, addressing these operational failures is not optional. It is something that requires attention now, not after the next task force or pilot.

At this point, administrative holds are less a policy failure than a governance failure, one that institutions can fix, but only if they treat operational clarity as a student success issue, not an internal inconvenience.

Go get a scoop

We keep hearing about the importance of grit for student success. In Edinburgh they have giant tubs of it on every street corner.

Different strokes

This is apparently Ithaka S+R week. Over at On EdTech, in my weekly Interesting Reads This Week post, I wrote about Ithaka S+R’s recent work on adult learners. One of the findings surprised me: I would have expected adult students to be concentrated primarily at public institutions, but as a share of enrollment (if not in absolute numbers), they are far more concentrated at private nonprofit institutions.

Ithaka S+R defines adult learners in the following way.

Adult learners are usually defined as students who are at least 25 years old at the time of enrollment, whether it’s their first time enrolling or not.

Adult students tend to have different needs than traditional-age students. A recent post from the National Association of Colleges & Employers (NACE) provides some useful context here. NACE defines nontraditional students as those aged 25 and older who are enrolled in undergraduate or graduate degree programs.

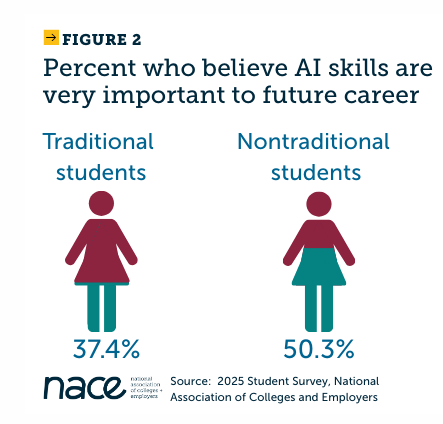

I don’t love the graphics, but a recent NACE survey highlights an interesting difference between traditional and nontraditional students: they vary in how important they believe AI-related skills will be for their future careers.

Given that generative AI has been broadly available for more than three years, it is possible that traditional-age students (18–24) no longer see it as an emerging technology. For them, AI may simply be part of the background environment, and their responses to questions about its importance likely reflect that normalization.

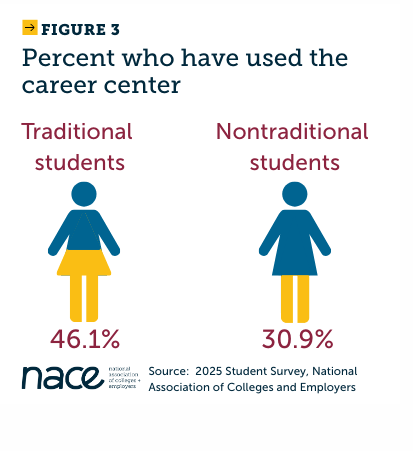

More troubling to me are the much larger differences between traditional-age and nontraditional students in their use of campus career centers. On this front, higher education institutions appear to be doing nontraditional students a real disservice.

This gap isn’t just about awareness or student motivation. It reflects how career services, and, more broadly, student success infrastructure, are still implicitly designed around full-time, traditional-age students with discretionary time, physical presence on campus, and long planning horizons.

How to lose 49,964 students in one reporting cycle

Inside Higher Ed’s The Key podcast recently featured an interesting episode on What Does a Student-Centered Data Strategy Look Like? The episode as a whole is worth listening to, but one comment from Mark Milliron, president of National University, particularly stuck with me. It underscored just how invisible many nontraditional students are, and how our metrics often make that invisibility worse.

Milliron observed that his institution enrolls roughly 50,000 students.

But when we report to IPEDS, of those 50,000 students, only 36 qualify to be reported on. 36, not 36 percent, 36. So part of what we're trying to do is we are on a mission to make sure that we see our students.

It does not serve anyone to have our primary accountability systems built around a shrinking minority of students. Metrics need to reflect the full range of students and modalities, and until they do so, real progress will be out of reach.

Parting thought

Taken together, these stories suggest that improving student success now depends less on discovering new interventions than on fixing the systems, assumptions, and metrics we already rely on.

Musical coda

I attended two different high schools, both in Zimbabwe. This is the choir from one of the schools I attended, giving their rendition of one of the songs from Hamilton. It’s wonderful.

Watching it took me straight back, every girl in that choir reminds me of those I went to school with.

If you found this post interesting or valuable, please share it as widely as possible, all I ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.